Continuous Integration

Continuous Integration, or CI, is generally defined as “a software development practice where members of a team integrate their work frequently [...] Each integration is verified by an automated build (including test) to detect integration errors as quickly as possible.”1 Simply put, the fundamental goal of CI is to automatically catch problematic changes as early as possible.

In practice, what does “integrating work frequently” mean for the modern, distributed application? Today’s systems have many moving pieces beyond just the latest versioned code in the repository. In fact, with the recent trend toward microservices, the changes that break an application are less likely to live inside the project’s immediate codebase and more likely to be in loosely coupled microservices on the other side of a network call. Whereas a traditional continuous build tests changes in your binary, an extension of this might test changes to upstream microservices. The dependency is just shifted from your function call stack to an HTTP request or Remote Procedure Calls (RPC).

Even further from code dependencies, an application might periodically ingest data or update machine learning models. It might execute on evolving operating systems, runtimes, cloud hosting services, and devices. It might be a feature that sits on top of a growing platform or be the platform that must accommodate a growing feature base. All of these things should be considered dependencies, and we should aim to “continuously integrate” their changes, too. Further complicating things, these changing components are often owned by developers outside our team, organization, or company and deployed on their own schedules.

So, perhaps a better definition for CI in today’s world, particularly when developing at scale, is the following:

Continuous Integration (2): the continuous assembling and testing of our entire complex and rapidly evolving ecosystem.

It is natural to conceptualize CI in terms of testing because the two are tightly coupled, and we’ll do so throughout this chapter. In previous chapters, we’ve discussed a comprehensive range of testing, from unit to integration, to larger-scoped systems.

From a testing perspective, CI is a paradigm to inform the following:

-

Which tests to run when in the development/release workflow, as code (and other) changes are continuously integrated into it

-

How to compose the system under test (SUT) at each point, balancing concerns like fidelity and setup cost

For example, which tests do we run on presubmit, which do we save for post-submit, and which do we save even later until our staging deploy? Accordingly, how do we represent our SUT at each of these points? As you might imagine, requirements for a presubmit SUT can differ significantly from those of a staging environment under test. For example, it can be dangerous for an application built from code pending review on presubmit to talk to real production backends (think security and quota vulnerabilities), whereas this is often acceptable for a staging environment.

And why should we try to optimize this often-delicate balance of testing “the right things” at “the right times” with CI? Plenty of prior work has already established the benefits of CI to the engineering organization and the overall business alike.2 These outcomes are driven by a powerful guarantee: verifiable—and timely—proof that the application is good to progress to the next stage. We don’t need to just hope that all contributors are very careful, responsible, and thorough; we can instead guarantee the working state of our application at various points from build throughout release, thereby improving confidence and quality in our products and productivity of our teams.

In the rest of this chapter, we’ll introduce some key CI concepts, best practices and challenges, before looking at how we manage CI at Google with an introduction to our continuous build tool, TAP, and an in-depth study of one application’s CI transformation.

CI Concepts

First, let’s begin by looking at some core concepts of CI.

Fast Feedback Loops

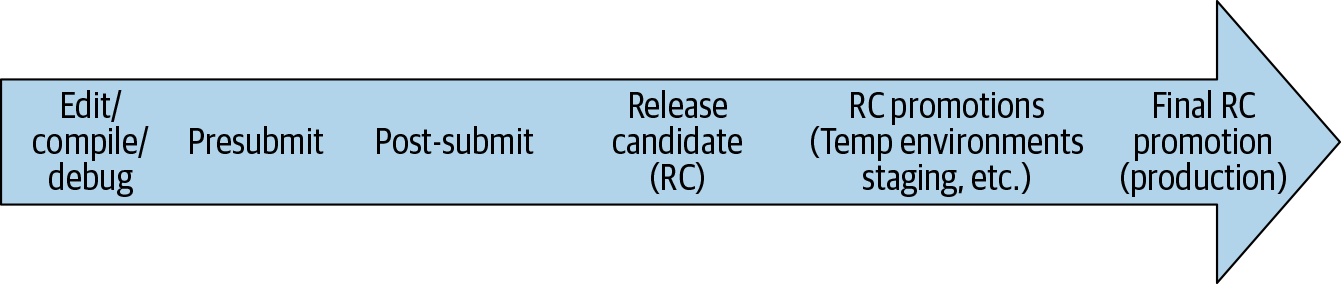

As discussed in Testing Overview, the cost of a bug grows almost exponentially the later it is caught. Figure 23-1 shows all the places a problematic code change might be caught in its lifetime.

In general, as issues progress to the "right" in our diagram, they become costlier for the following reasons:

-

They must be triaged by an engineer who is likely unfamiliar with the problematic code change.

-

They require more work for the code change author to recollect and investigate the change.

-

They negatively affect others, whether engineers in their work or ultimately the end user.

To minimize the cost of bugs, CI encourages us to use fast feedback loops.3 Each time we integrate a code (or other) change into a testing scenario and observe the results, we get a new feedback loop. Feedback can take many forms; following are some common ones (in order of fastest to slowest):

-

The edit-compile-debug loop of local development

-

Automated test results to a code change author on presubmit

-

An integration error between changes to two projects, detected after both are submitted and tested together (i.e., on post-submit)

-

An incompatibility between our project and an upstream microservice dependency, detected by a QA tester in our staging environment, when the upstream service deploys its latest changes

-

Bug reports by internal users who are opted in to a feature before external users

-

Bug or outage reports by external users or the press

Canarying—or deploying to a small percentage of production first—can help minimize issues that do make it to production, with a subset-of-production initial feedback loop preceding all-of-production. However, canarying can cause problems, too, particularly around compatibility between deployments when multiple versions are deployed at once. This is sometimes known as version skew, a state of a distributed system in which it contains multiple incompatible versions of code, data, and/or configuration. Like many issues we look at in this book, version skew is another example of a challenging problem that can arise when trying to develop and manage software over time.

Experiments and feature flags are extremely powerful feedback loops. They reduce deployment risk by isolating changes within modular components that can be dynamically toggled in production. Relying heavily on feature-flag-guarding is a common paradigm for Continuous Delivery, which we explore further in Continuous Delivery.

Accessible and actionable feedback

It’s also important that feedback from CI be widely accessible. In addition to our open culture around code visibility, we feel similarly about our test reporting. We have a unified test reporting system in which anyone can easily look up a build or test run, including all logs (excluding user Personally Identifiable Information [PII]), whether for an individual engineer’s local run or on an automated development or staging build.

Along with logs, our test reporting system provides a detailed history of when build or test targets began to fail, including audits of where the build was cut at each run, where it was run, and by whom. We also have a system for flake classification, which uses statistics to classify flakes at a Google-wide level, so engineers don’t need to figure this out for themselves to determine whether their change broke another project’s test (if the test is flaky: probably not).

Visibility into test history empowers engineers to share and collaborate on feedback, an essential requirement for disparate teams to diagnose and learn from integration failures between their systems. Similarly, bugs (e.g., tickets or issues) at Google are open with full comment history for all to see and learn from (with the exception, again, of customer PII).

Finally, any feedback from CI tests should not just be accessible but actionable—easy to use to find and fix problems. We’ll look at an example of improving user-unfriendly feedback in our case study later in this chapter. By improving test output readability, you automate the understanding of feedback.

Automation

It’s well known that automating development-related tasks saves engineering resources in the long run. Intuitively, because we automate processes by defining them as code, peer review when changes are checked in will reduce the probability of error. Of course, automated processes, like any other software, will have bugs; but when implemented effectively, they are still faster, easier, and more reliable than if they were attempted manually by engineers.

CI, specifically, automates the build and release processes, with a Continuous Build and Continuous Delivery. Continuous testing is applied throughout, which we’ll look at in the next section.

Continuous Build

The Continuous Build (CB) integrates the latest code changes at head4 and runs an automated build and test. Because the CB runs tests as well as building code, “breaking the build” or “failing the build” includes breaking tests as well as breaking compilation.

After a change is submitted, the CB should run all relevant tests. If a change passes all tests, the CB marks it passing or “green,” as it is often displayed in user interfaces (UIs). This process effectively introduces two different versions of head in the repository: true head, or the latest change that was committed, and green head, or the latest change the CB has verified. Engineers are able to sync to either version in their local development. It’s common to sync against green head to work with a stable environment, verified by the CB, while coding a change but have a process that requires changes to be synced to true head before submission.

Continuous Delivery

The first step in Continuous Delivery (CD; discussed more fully in Continuous Delivery) is release automation, which continuously assembles the latest code and configuration from head into release candidates. At Google, most teams cut these at green, as opposed to true, head.

Release candidate (RC): A cohesive, deployable unit created by an automated process,5 assembled of code, configuration, and other dependencies that have passed the continuous build.

Note that we include configuration in release candidates—this is extremely important, even though it can slightly vary between environments as the candidate is promoted. We’re not necessarily advocating you compile configuration into your binaries—actually, we would recommend dynamic configuration, such as experiments or feature flags, for many scenarios.6

Rather, we are saying that any static configuration you do have should be promoted as part of the release candidate so that it can undergo testing along with its corresponding code. Remember, a large percentage of production bugs are caused by “silly” configuration problems, so it’s just as important to test your configuration as it is your code (and to test it along with the same code that will use it). Version skew is often caught in this release-candidate-promotion process. This assumes, of course, that your static configuration is in version control—at Google, static configuration is in version control along with the code, and hence goes through the same code review process.

We then define CD as follows:

Continuous Delivery (CD): a continuous assembling of release candidates, followed by the promotion and testing of those candidates throughout a series of environments—sometimes reaching production and sometimes not.

The promotion and deployment process often depends on the team. We’ll show how our case study navigated this process.

For teams at Google that want continuous feedback from new changes in production (e.g., Continuous Deployment), it’s usually infeasible to continuously push entire binaries, which are often quite large, on green. For that reason, doing a selective Continuous Deployment, through experiments or feature flags, is a common strategy.7

As an RC progresses through environments, its artifacts (e.g., binaries, containers) ideally should not be recompiled or rebuilt. Using containers such as Docker helps enforce consistency of an RC between environments, from local development onward. Similarly, using orchestration tools like Kubernetes (or in our case, usually Borg), helps enforce consistency between deployments. By enforcing consistency of our release and deployment between environments, we achieve higher-fidelity earlier testing and fewer surprises in production.

Continuous Testing

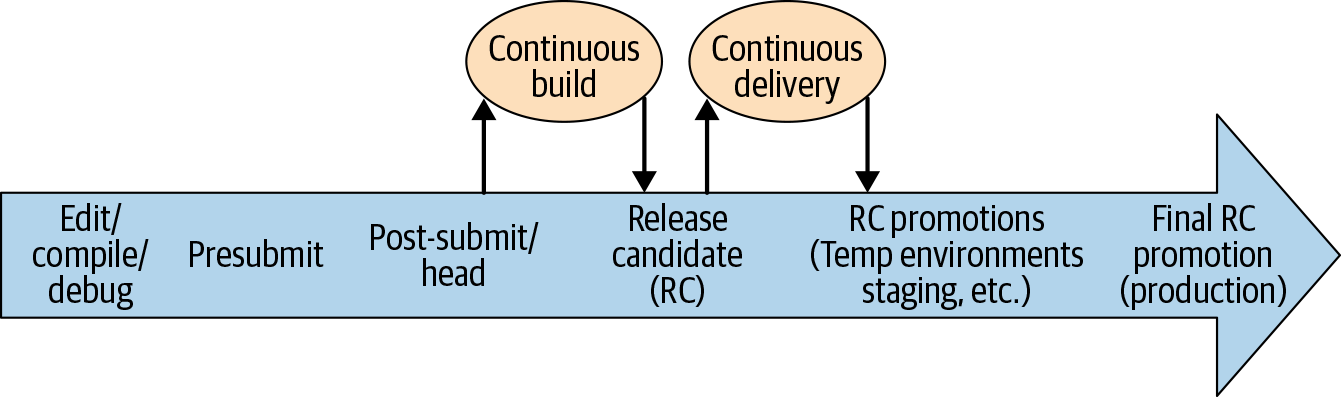

Let’s look at how CB and CD fit in as we apply Continuous Testing (CT) to a code change throughout its lifetime, as shown Figure 23-2.

The rightward arrow shows the progression of a single code change from local development to production. Again, one of our key objectives in CI is determining what to test when in this progression. Later in this chapter, we’ll introduce the different testing phases and provide some considerations for what to test in presubmit versus post-submit, and in the RC and beyond. We’ll show that, as we shift to the right, the code change is subjected to progressively larger-scoped automated tests.

Why presubmit isn’t enough

With the objective to catch problematic changes as soon as possible and the ability to run automated tests on presubmit, you might be wondering: why not just run all tests on presubmit?

The main reason is that it’s too expensive. Engineer productivity is extremely valuable, and waiting a long time to run every test during code submission can be severely disruptive. Further, by removing the constraint for presubmits to be exhaustive, a lot of efficiency gains can be made if tests pass far more frequently than they fail. For example, the tests that are run can be restricted to certain scopes, or selected based on a model that predicts their likelihood of detecting a failure.

Similarly, it’s expensive for engineers to be blocked on presubmit by failures arising from instability or flakiness that has nothing to do with their code change.

Another reason is that during the time we run presubmit tests to confirm that a change is safe, the underlying repository might have changed in a manner that is incompatible with the changes being tested. That is, it is possible for two changes that touch completely different files to cause a test to fail. We call this a mid-air collision, and though generally rare, it happens most days at our scale. CI systems for smaller repositories or projects can avoid this problem by serializing submits so that there is no difference between what is about to enter and what just did.

Presubmit versus post-submit

So, which tests should be run on presubmit? Our general rule of thumb is: only fast, reliable ones. You can accept some loss of coverage on presubmit, but that means you need to catch any issues that slip by on post-submit, and accept some number of rollbacks. On post-submit, you can accept longer times and some instability, as long as you have proper mechanisms to deal with it.

Note

We’ll show how TAP and our case study handle failure management in CI at Google.

We don’t want to waste valuable engineer productivity by waiting too long for slow tests or for too many tests—we typically limit presubmit tests to just those for the project where the change is happening. We also run tests concurrently, so there is a resource decision to consider as well. Finally, we don’t want to run unreliable tests on presubmit, because the cost of having many engineers affected by them, debugging the same problem that is not related to their code change, is too high.

Most teams at Google run their small tests (like unit tests) on presubmit8—these are the obvious ones to run as they tend to be the fastest and most reliable. Whether and how to run larger-scoped tests on presubmit is the more interesting question, and this varies by team. For teams that do want to run them, hermetic testing is a proven approach to reducing their inherent instability. Another option is to allow large-scoped tests to be unreliable on presubmit but disable them aggressively when they start failing.

Release candidate testing

After a code change has passed the CB (this might take multiple cycles if there were failures), it will soon encounter CD and be included in a pending release candidate.

As CD builds RCs, it will run larger tests against the entire candidate. We test a release candidate by promoting it through a series of test environments and testing it at each deployment. This can include a combination of sandboxed, temporary environments and shared test environments, like dev or staging. It’s common to include some manual QA testing of the RC in shared environments, too.

There are several reasons why it’s important to run a comprehensive, automated test suite against an RC, even if it is the same suite that CB just ran against the code on post-submit (assuming the CD cuts at green):

- As a sanity check

- We double check that nothing strange happened when the code was cut and recompiled in the RC.

- For auditability

- If an engineer wants to check an RC’s test results, they are readily available and associated with the RC, so they don’t need to dig through CB logs to find them.

- To allow for cherry picks

- If you apply a cherry-pick fix to an RC, your source code has now diverged from the latest cut tested by the CB.

- For emergency pushes

- In that case, CD can cut from true head and run the minimal set of tests necessary to feel confident about an emergency push, without waiting for the full CB to pass.

Production testing

Our continuous, automated testing process goes all the way to the final deployed environment: production. We should run the same suite of tests against production (sometimes called probers) that we did against the release candidate earlier on to verify: 1) the working state of production, according to our tests, and 2) the relevance of our tests, according to production.

Continuous testing at each step of the application’s progression, each with its own trade-offs, serves as a reminder of the value in a “defense in depth” approach to catching bugs—it isn’t just one bit of technology or policy that we rely upon for quality and stability, it’s many testing approaches combined.

CI Challenges

We’ve discussed some of the established best practices in CI and have introduced some of the challenges involved, such as the potential disruption to engineer productivity of unstable, slow, conflicting, or simply too many tests at presubmit. Some common additional challenges when implementing CI include the following:

-

Presubmit optimization, including which tests to run at presubmit time given the potential issues we’ve already described, and how to run them.

-

Culprit finding and failure isolation: Which code or other change caused the problem, and which system did it happen in? “Integrating upstream microservices" is one approach to failure isolation in a distributed architecture, when you want to figure out whether a problem originated in your own servers or a backend. In this approach, you stage combinations of your stable servers along with upstream microservices’ new servers. (Thus, you are integrating the microservices’ latest changes into your testing.) This approach can be particularly challenging due to version skew: not only are these environments often incompatible, but you’re also likely to encounter false positives—problems that occur in a particular staged combination that wouldn’t actually be spotted in production.

-

Resource constraints: Tests need resources to run, and large tests can be very expensive. In addition, the cost for the infrastructure for inserting automated testing throughout the process can be considerable.

There’s also the challenge of failure management—what to do when tests fail. Although smaller problems can usually be fixed quickly, many of our teams find that it’s extremely difficult to have a consistently green test suite when large end-to-end tests are involved. They inherently become broken or flaky and are difficult to debug; there needs to be a mechanism to temporarily disable and keep track of them so that the release can go on. A common technique at Google is to use bug “hotlists” filed by an on-call or release engineer and triaged to the appropriate team. Even better is when these bugs can be automatically generated and filed—some of our larger products, like Google Web Server (GWS) and Google Assistant, do this. These hotlists should be curated to make sure any release-blocking bugs are fixed immediately. Nonrelease blockers should be fixed, too; they are less urgent, but should also be prioritized so the test suite remains useful and is not simply a growing pile of disabled, old tests. Often, the problems caught by end-to-end test failures are actually with tests rather than code.

Flaky tests pose another problem to this process. They erode confidence similar to a broken test, but finding a change to roll back is often more difficult because the failure won’t happen all the time. Some teams rely on a tool to remove such flaky tests from presubmit temporarily while the flakiness is investigated and fixed. This keeps confidence high while allowing for more time to fix the problem.

Test instability is another significant challenge that we’ve already looked at in the context of presubmits. One tactic for dealing with this is to allow multiple attempts of the test to run. This is a common test configuration setting that teams use. Also, within test code, retries can be introduced at various points of specificity.

Another approach that helps with test instability (and other CI challenges) is hermetic testing, which we’ll look at in the next section.

Hermetic Testing

Because talking to a live backend is unreliable, we often use hermetic backends for larger-scoped tests. This is particularly useful when we want to run these tests on presubmit, when stability is of utmost importance. In Testing Overview, we introduced the concept of hermetic tests:

Hermetic tests: tests run against a test environment (i.e., application servers and resources) that is entirely self-contained (i.e., no external dependencies like production backends).

Hermetic tests have two important properties: greater determinism (i.e., stability) and isolation. Hermetic servers are still prone to some sources of nondeterminism, like system time, random number generation, and race conditions. But, what goes into the test doesn’t change based on outside dependencies, so when you run a test twice with the same application and test code, you should get the same results. If a hermetic test fails, you know that it’s due to a change in your application code or tests (with a minor caveat: they can also fail due to a restructuring of your hermetic test environment, but this should not change very often). For this reason, when CI systems rerun tests hours or days later to provide additional signals, hermeticity makes test failures easier to narrow down.

The other important property, isolation, means that problems in production should not affect these tests. We generally run these tests all on the same machine as well, so we don’t have to worry about network connectivity issues. The reverse also holds: problems caused by running hermetic tests should not affect production.

Hermetic test success should not depend on the user running the test. This allows people to reproduce tests run by the CI system and allows people (e.g., library developers) to run tests owned by other teams.

One type of hermetic backend is a fake. As discussed in Test Doubles, these can be cheaper than running a real backend, but they take work to maintain and have limited fidelity.

The cleanest option to achieve a presubmit-worthy integration test is with a fully hermetic setup—that is, starting up the entire stack sandboxed11—and Google provides out-of-the-box sandbox configurations for popular components, like databases, to make it easier. This is more feasible for smaller applications with fewer components, but there are exceptions at Google, even one (by DisplayAds) that starts about four hundred servers from scratch on every presubmit as well as continuously on post-submit. Since the time that system was created, though, record/replay has emerged as a more popular paradigm for larger systems and tends to be cheaper than starting up a large sandboxed stack.

Record/replay (see Larger Testing) systems record live backend responses, cache them, and replay them in a hermetic test environment. Record/replay is a powerful tool for reducing test instability, but one downside is that it leads to brittle tests: it’s difficult to strike a balance between the following:

- False positives

- The test passes when it probably shouldn’t have because we are hitting the cache too much and missing problems that would surface when capturing a new response.

- False negatives

- The test fails when it probably shouldn’t have because we are hitting the cache too little. This requires responses to be updated, which can take a long time and lead to test failures that must be fixed, many of which might not be actual problems. This process is often submit-blocking, which is not ideal.

Ideally, a record/replay system should detect only problematic changes and cache-miss only when a request has changed in a meaningful way. In the event that that change causes a problem, the code change author would rerun the test with an updated response, see that the test is still failing, and thereby be alerted to the problem. In practice, knowing when a request has changed in a meaningful way can be incredibly difficult in a large and ever-changing system.

As we’ve seen in this section, hermetic testing can both reduce instability in larger-scoped tests and help isolate failures—addressing two of the significant CI challenges we identified in the previous section. However, hermetic backends can also be more expensive because they use more resources and are slower to set up. Many teams use combinations of hermetic and live backends in their test environments.

CI at Google

Now let’s look in more detail at how CI is implemented at Google. First, we’ll look at our global continuous build, TAP, used by the vast majority of teams at Google, and how it enables some of the practices and addresses some of the challenges that we looked at in the previous section. We’ll also look at one application, Google Takeout, and how a CI transformation helped it scale both as a platform and as a service.

CI Case Study: Google Takeout

Google Takeout started out as a data backup and download product in 2011. Its founders pioneered the idea of “data liberation”—that users should be able to easily take their data with them, in a usable format, wherever they go. They began by integrating Takeout with a handful of Google products themselves, producing archives of users’ photos, contact lists, and so on for download at their request. However, Takeout didn’t stay small for long, growing as both a platform and a service for a wide variety of Google products. As we’ll see, effective CI is central to keeping any large project healthy, but is especially critical when applications rapidly grow.

Scenario #1: Continuously broken dev deploys

Problem: As Takeout gained a reputation as a powerful Google-wide data fetching, archiving, and download tool, other teams at the company began to turn to it, requesting APIs so that their own applications could provide backup and download functionality, too, including Google Drive (folder downloads are served by Takeout) and Gmail (for ZIP file previews). All in all, Takeout grew from being the backend for just the original Google Takeout product, to providing APIs for at least 10 other Google products, offering a wide range of functionality.

The team decided to deploy each of the new APIs as a customized instance, using the same original Takeout binaries but configuring them to work a little differently. For example, the environment for Drive bulk downloads has the largest fleet, the most quota reserved for fetching files from the Drive API, and some custom authentication logic to allow non-signed-in users to download public folders.

Before long, Takeout faced “flag issues.” Flags added for one of the instances would break the others, and their deployments would break when servers could not start up due to configuration incompatibilities. Beyond feature configuration, there was security and ACL configuration, too. For example, the consumer Drive download service should not have access to keys that encrypt enterprise Gmail exports. Configuration quickly became complicated and led to nearly nightly breakages.

Some efforts were made to detangle and modularize configuration, but the bigger problem this exposed was that when a Takeout engineer wanted to make a code change, it was not practical to manually test that each server started up under each configuration. They didn’t find out about configuration failures until the next day’s deploy. There were unit tests that ran on presubmit and post-submit (by TAP), but those weren’t sufficient to catch these kinds of issues.

What the team did

The team created temporary, sandboxed mini-environments for each of these instances that ran on presubmit and tested that all servers were healthy on startup. Running the temporary environments on presubmit prevented 95% of broken servers from bad configuration and reduced nightly deployment failures by 50%.

Although these new sandboxed presubmit tests dramatically reduced deployment failures, they didn’t remove them entirely. In particular, Takeout’s end-to-end tests would still frequently break the deploy, and these tests were difficult to run on presubmit (because they use test accounts, which still behave like real accounts in some respects and are subject to the same security and privacy safeguards). Redesigning them to be presubmit friendly would have been too big an undertaking.

If the team couldn’t run end-to-end tests in presubmit, when could it run them? It wanted to get end-to-end test results more quickly than the next day’s dev deploy and decided every two hours was a good starting point. But the team didn’t want to do a full dev deploy this often—this would incur overhead and disrupt long-running processes that engineers were testing in dev. Making a new shared test environment for these tests also seemed like too much overhead to provision resources for, plus culprit finding (i.e., finding the deployment that led to a failure) could involve some undesirable manual work.

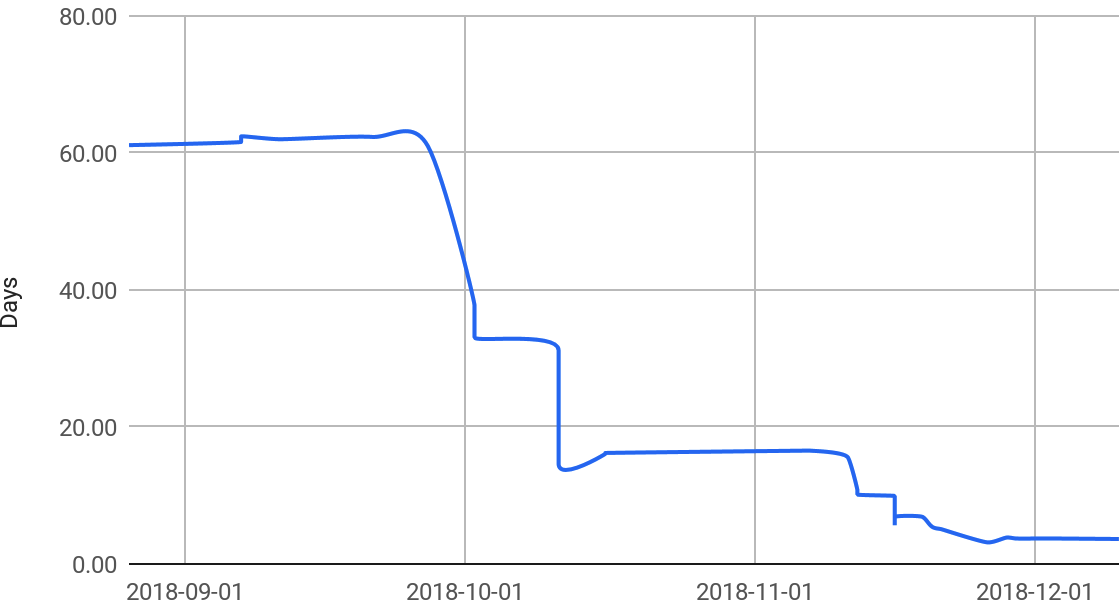

So, the team reused the sandboxed environments from presubmit, easily extending them to a new post-submit environment. Unlike presubmit, post-submit was compliant with security safeguards to use the test accounts (for one, because the code has been approved), so the end-to-end tests could be run there. The post-submit CI runs every two hours, grabbing the latest code and configuration from green head, creates an RC, and runs the same end-to-end test suite against it that is already run in dev.

Lesson learned

Faster feedback loops prevent problems in dev deploys:

-

Moving tests for different Takeout products from “after nightly deploy” to presubmit prevented 95% of broken servers from bad configuration and reduced nightly deployment failures by 50%.

-

Though end-to-end tests couldn’t be moved all the way to presubmit, they were still moved from “after nightly deploy” to “post-submit within two hours.” This effectively cut the “culprit set” by 12 times.

Scenario #2: Indecipherable test logs

Problem: As Takeout incorporated more Google products, it grew into a mature platform that allowed product teams to insert plug-ins, with product-specific data-fetching code, directly into Takeout's binary. For example, the Google Photos plug-in knows how to fetch photos, album metadata, and the like. Takeout expanded from its original “handful” of products to now integrate with more than 90.

Takeout’s end-to-end tests dumped its failures to a log, and this approach didn’t scale to 90 product plug-ins. As more products integrated, more failures were introduced. Even though the team was running the tests earlier and more often with the addition of the post-submit CI, multiple failures would still pile up inside and were easy to miss. Going through these logs became a frustrating time sink, and the tests were almost always failing.

What the team did

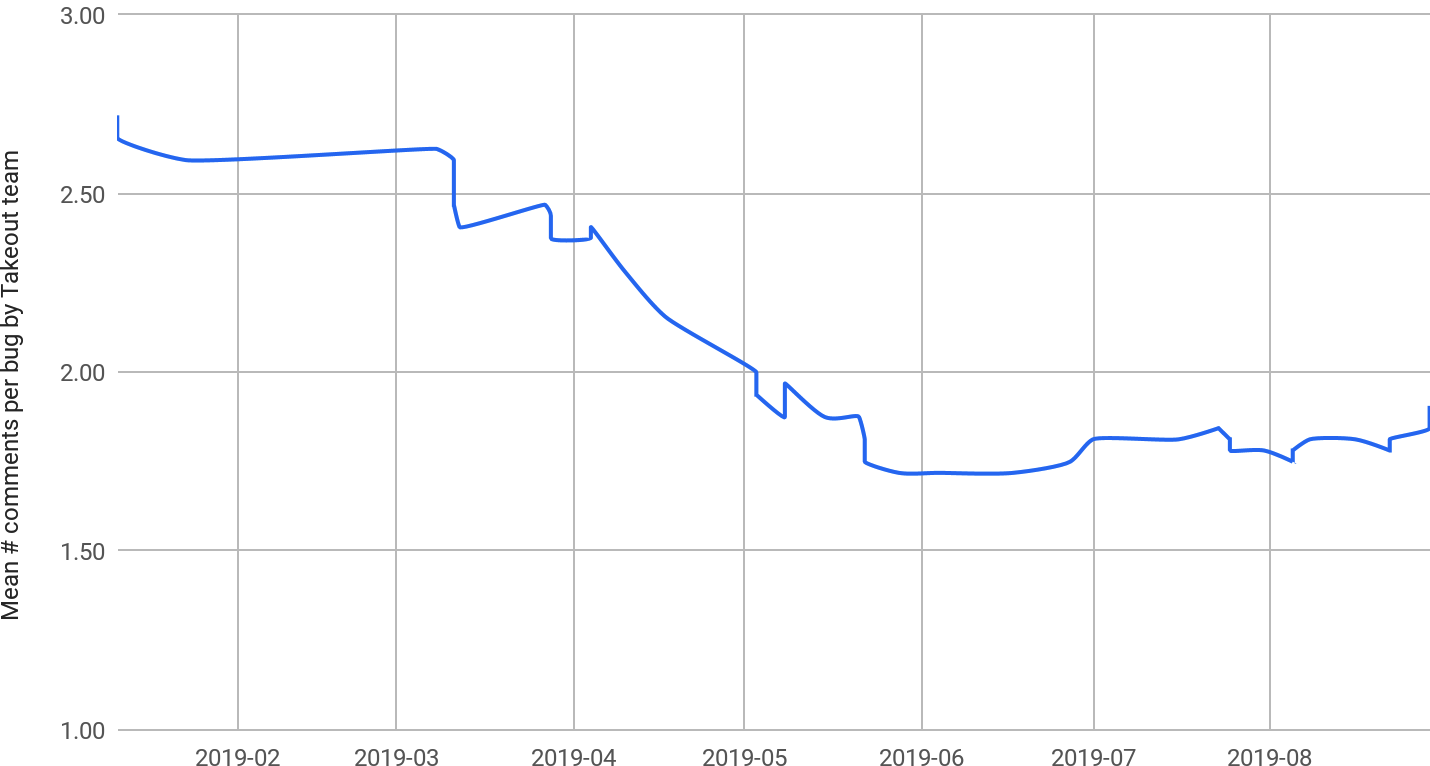

The team refactored the tests into a dynamic, configuration-based suite (using a parameterized test runner) that reported results in a friendlier UI, clearly showing individual test results as green or red: no more digging through logs. They also made failures much easier to debug, most notably, by displaying failure information, with links to logs, directly in the error message. For example, if Takeout failed to fetch a file from Gmail, the test would dynamically construct a link that searched for that file’s ID in the Takeout logs and include it in the test failure message. This automated much of the debugging process for product plug-in engineers and required less of the Takeout team’s assistance in sending them logs, as demonstrated in Figure 23-3.

Lesson learned

Accessible, actionable feedback from CI reduces test failures and improves productivity. These initiatives reduced the Takeout team’s involvement in debugging client (product plug-in) test failures by 35%.

Scenario #3: Debugging “all of Google”

Problem: An interesting side effect of the Takeout CI that the team did not anticipate was that, because it verified the output of 90-some odd end-user–facing products, in the form of an archive, they were basically testing “all of Google” and catching issues that had nothing to do with Takeout. This was a good thing—Takeout was able to help contribute to the quality of Google’s products overall. However, this introduced a problem for their CI processes: they needed better failure isolation so that they could determine which problems were in their build (which were the minority) and which lay in loosely coupled microservices behind the product APIs they called.

What the team did

The team’s solution was to run the exact same test suite continuously against production as it already did in its post-submit CI. This was cheap to implement and allowed the team to isolate which failures were new in its build and which were in production; for instance, the result of a microservice release somewhere else “in Google.”

Lesson learned

Running the same test suite against prod and a post-submit CI (with newly built binaries, but the same live backends) is a cheap way to isolate failures.

Remaining challenge

Going forward, the burden of testing “all of Google” (obviously, this is an exaggeration, as most product problems are caught by their respective teams) grows as Takeout integrates with more products and as those products become more complex. Manual comparisons between this CI and prod are an expensive use of the Build Cop’s time.

Future improvement

This presents an interesting opportunity to try hermetic testing with record/replay in Takeout’s post-submit CI. In theory, this would eliminate failures from backend product APIs surfacing in Takeout’s CI, which would make the suite more stable and effective at catching failures in the last two hours of Takeout changes—which is its intended purpose.

Scenario #4: Keeping it green

Problem: As the platform supported more product plug-ins, which each included end-to-end tests, these tests would fail and the end-to-end test suites were nearly always broken. The failures could not all be immediately fixed. Many were due to bugs in product plug-in binaries, which the Takeout team had no control over. And some failures mattered more than others—low-priority bugs and bugs in the test code did not need to block a release, whereas higher-priority bugs did. The team could easily disable tests by commenting them out, but that would make the failures too easy to forget about.

One common source of failures: tests would break when product plug-ins were rolling out a feature. For example, a playlist-fetching feature for the YouTube plug-in might be enabled for testing in dev for a few months before being enabled in prod. The Takeout tests only knew about one result to check, so that often resulted in the test needing to be disabled in particular environments and manually curated as the feature rolled out.

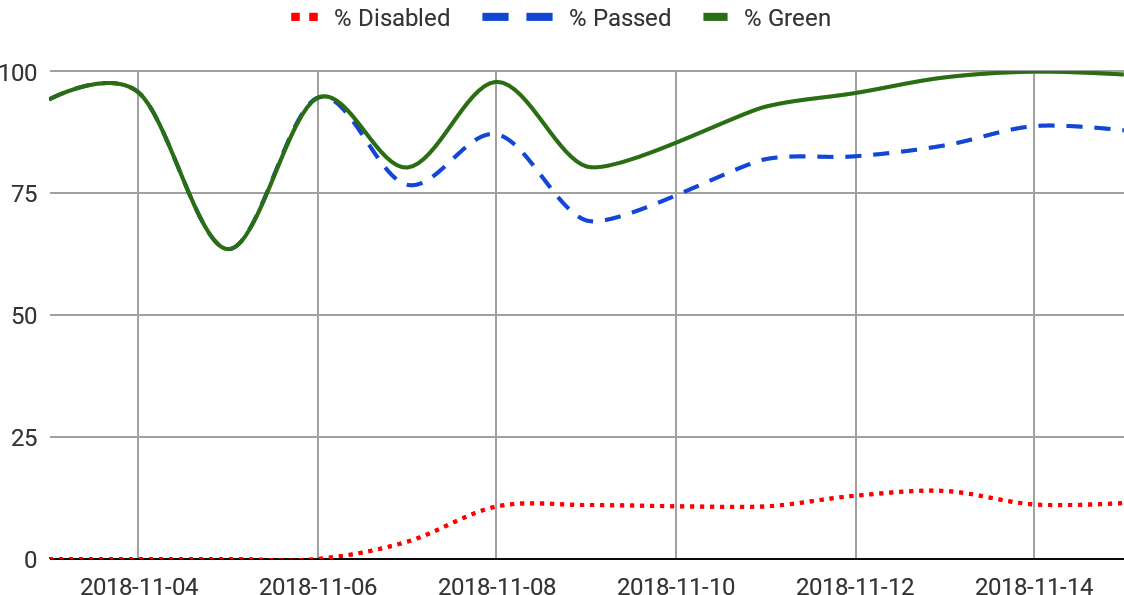

What the team did

The team came up with a strategic way to disable failing tests by tagging them with an associated bug and filing that off to the responsible team (usually a product plug-in team). When a failing test was tagged with a bug, the team’s testing framework would suppress its failure. This allowed the test suite to stay green and still provide confidence that everything else, besides the known issues, was passing, as illustrated in Figure 23-4.

For the rollout problem, the team added capability for plug-in engineers to specify the name of a feature flag, or ID of a code change, that enabled a particular feature along with the output to expect both with and without the feature. The tests were equipped to query the test environment to determine whether the given feature was enabled there and verified the expected output accordingly.

When bug tags from disabled tests began to accumulate and were not updated, the team automated their cleanup. The tests would now check whether a bug was closed by querying our bug system’s API. If a tagged-failing test actually passed and was passing for longer than a configured time limit, the test would prompt to clean up the tag (and mark the bug fixed, if it wasn’t already). There was one exception for this strategy: flaky tests. For these, the team would allow a test to be tagged as flaky, and the system wouldn’t prompt a tagged “flaky” failure for cleanup if it passed.

These changes made a mostly self-maintaining test suite, as illustrated in Figure 23-5.

Lessons learned

Disabling failing tests that can’t be immediately fixed is a practical approach to keeping your suite green, which gives confidence that you’re aware of all test failures. Also, automating the test suite’s maintenance, including rollout management and updating tracking bugs for fixed tests, keeps the suite clean and prevents technical debt. In DevOps parlance, we could call the metric in Figure 23-5 MTTCU: mean time to clean up.

Future improvement

Automating the filing and tagging of bugs would be a helpful next step. This is still a manual and burdensome process. As mentioned earlier, some of our larger teams already do this.

Further challenges

The scenarios we’ve described are far from the only CI challenges faced by Takeout, and there are still more problems to solve. For example, we mentioned the difficulty of isolating failures from upstream services in CI Challenges. This is a problem that Takeout still faces with rare breakages originating with upstream services, such as when a security update in the streaming infrastructure used by Takeout’s “Drive folder downloads” API broke archive decryption when it deployed to production. The upstream services are staged and tested themselves, but there is no simple way to automatically check with CI if they are compatible with Takeout after they're launched into production. An initial solution involved creating an “upstream staging” CI environment to test production Takeout binaries against the staged versions of their upstream dependencies. However, this proved difficult to maintain, with additional compatibility issues between staging and production versions.

But I Can’t Afford CI

You might be thinking that’s all well and good, but you have neither the time nor money to build any of this. We certainly acknowledge that Google might have more resources to implement CI than the typical startup does. Yet many of our products have grown so quickly that they didn’t have time to develop a CI system either (at least not an adequate one).

In your own products and organizations, try and think of the cost you are already paying for problems discovered and dealt with in production. These negatively affect the end user or client, of course, but they also affect the team. Frequent production fire-fighting is stressful and demoralizing. Although building out CI systems is expensive, it’s not necessarily a new cost as much as a cost shifted left to an earlier—and more preferable—stage, reducing the incidence, and thus the cost, of problems occurring too far to the right. CI leads to a more stable product and happier developer culture in which engineers feel more confident that “the system” will catch problems, and they can focus more on features and less on fixing.

Conclusion

Even though we’ve described our CI processes and some of how we’ve automated them, none of this is to say that we have developed perfect CI systems. After all, a CI system itself is just software and is never complete and should be adjusted to meet the evolving demands of the application and engineers it is meant to serve. We’ve tried to illustrate this with the evolution of Takeout’s CI and the future areas of improvement we point out.

TL;DRs

-

A CI system decides what tests to use, and when.

-

CI systems become progressively more necessary as your codebase ages and grows in scale.

-

CI should optimize quicker, more reliable tests on presubmit and slower, less deterministic tests on post-submit.

-

Accessible, actionable feedback allows a CI system to become more efficient.

1https://www.martinfowler.com/articles/continuousIntegration.html

2Forsgren, Nicole, et al. (2018). Accelerate: The Science of Lean Software and DevOps: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations. IT Revolution.

3This is also sometimes called “shifting left on testing.”

4Head is the latest versioned code in our monorepo. In other workflows, this is also referred to as master, mainline, or trunk. Correspondingly, integrating at head is also known as trunk-based development.

5At Google, release automation is managed by a separate system from TAP. We won’t focus on how release automation assembles RCs, but if you’re interested, we do refer you to Site Reliability Engineering (O'Reilly) in which our release automation technology (a system called Rapid) is discussed in detail.

6CD with experiments and feature flags is discussed further in Continuous Delivery.

7We call these “mid-air collisions” because the probability of it occurring is extremely low; however, when this does happen, the results can be quite surprising.

8Each team at Google configures a subset of its project’s tests to run on presubmit (versus post-submit). In reality, our continuous build actually optimizes some presubmit tests to be saved for post-submit, behind the scenes. We'll further discuss this later on in this chapter.

9Aiming for 100% uptime is the wrong target. Pick something like 99.9% or 99.999% as a business or product trade-off, define and monitor your actual uptime, and use that “budget” as an input to how aggressively you’re willing to push risky releases.

10We believe CI is actually critical to the software engineering ecosystem: a must-have, not a luxury. But that is not universally understood yet.

11In practice, it’s often difficult to make a completely sandboxed test environment, but the desired stability can be achieved by minimizing outside dependencies.

12Any change to Google’s codebase can be rolled back with two clicks!