Build Systems and Build Philosophy

If you ask Google engineers what they like most about working at Google (besides the free food and cool products), you might hear something surprising: engineers love the build system.1 Google has spent a tremendous amount of engineering effort over its lifetime in creating its own build system from the ground up, with the goal of ensuring that our engineers are able to quickly and reliably build code. The effort has been so successful that Blaze, the main component of the build system, has been reimplemented several different times by ex-Googlers who have left the company.2 In 2015, Google finally open sourced an implementation of Blaze named Bazel.

Purpose of a Build System

Fundamentally, all build systems have a straightforward purpose: they transform the source code written by engineers into executable binaries that can be read by machines. A good build system will generally try to optimize for two important properties:

- Fast

- A developer should be able to type a single command to run the build and get back the resulting binary, often in as little as a few seconds.

- Correct

- Every time any developer runs a build on any machine, they should get the same result (assuming that the source files and other inputs are the same).

Many older build systems attempt to make trade-offs between speed and correctness by taking shortcuts that can lead to inconsistent builds. Bazel’s main objective is to avoid having to choose between speed and correctness, providing a build system structured to ensure that it’s always possible to build code efficiently and consistently.

Build systems aren’t just for humans; they also allow machines to create builds automatically, whether for testing or for releases to production. In fact, the large majority of builds at Google are triggered automatically rather than directly by engineers. Nearly all of our development tools tie into the build system in some way, giving huge amounts of value to everyone working on our codebase. Here’s a small sample of workflows that take advantage of our automated build system:

-

Code is automatically built, tested, and pushed to production without any human intervention. Different teams do this at different rates: some teams push weekly, others daily, and others as fast as the system can create and validate new builds. (see Continuous Delivery).

-

Developer changes are automatically tested when they’re sent for code review (see Critique: Google’s Code Review Tool) so that both the author and reviewer can immediately see any build or test issues caused by the change.

-

Changes are tested again immediately before merging them into the trunk, making it much more difficult to submit breaking changes.

-

Authors of low-level libraries are able to test their changes across the entire codebase, ensuring that their changes are safe across millions of tests and binaries.

-

Engineers are able to create large-scale changes (LSCs) that touch tens of thousands of source files at a time (e.g., renaming a common symbol) while still being able to safely submit and test those changes. We discuss LSCs in greater detail in Large-Scale Changes.

All of this is possible only because of Google’s investment in its build system. Although Google might be unique in its scale, any organization of any size can realize similar benefits by making proper use of a modern build system. This chapter describes what Google considers to be a "modern build system" and how to use such systems.

What Happens Without a Build System?

Build systems allow your development to scale. As we’ll illustrate in the next section, we run into problems of scaling without a proper build environment.

But All I Need Is a Compiler!

The need for a build system might not be immediately obvious. After all, most of us probably didn’t use a build system when we were first learning to code—we probably started by invoking tools like gcc or javac directly from the command line, or the equivalent in an integrated development environment (IDE). As long as all of our source code is in the same directory, a command like this works fine:

javac *.java

This instructs the Java compiler to take every Java source file in the current directory and turn it into a binary class file. In the simplest case, this is all that we need.

However, things become more complicated quickly as soon as our code expands. javac is smart enough to look in subdirectories of our current directory to find code that we import. But it has no way of finding code stored in other parts of the filesystem (perhaps a library shared by several of our projects). It also obviously only knows how to build Java code. Large systems often involve different pieces written in a variety of programming languages with webs of dependencies among those pieces, meaning no compiler for a single language can possibly build the entire system.

As soon as we end up having to deal with code from multiple languages or multiple compilation units, building code is no longer a one-step process. We now need to think about what our code depends on and build those pieces in the proper order, possibly using a different set of tools for each piece. If we change any of the dependencies, we need to repeat this process to avoid depending on stale binaries. For a codebase of even moderate size, this process quickly becomes tedious and error-prone.

The compiler also doesn’t know anything about how to handle external dependencies, such as third-party JAR files in Java. Often the best we can do without a build system is to download the dependency from the internet, stick it in a lib folder on the hard drive, and configure the compiler to read libraries from that directory. Over time, it’s easy to forget what libraries we put in there, where they came from, and whether they’re still in use. And good luck keeping them up to date as the library maintainers release new versions.

Shell Scripts to the Rescue?

Suppose that your hobby project starts out simple enough that you can build it using just a compiler, but you begin running into some of the problems described previously. Maybe you still don’t think you need a real build system and can automate away the tedious parts using some simple shell scripts that take care of building things in the correct order. This helps out for a while, but pretty soon you start running into even more problems:

-

It becomes tedious. As your system grows more complex, you begin spending almost as much time working on your build scripts as on real code. Debugging shell scripts is painful, with more and more hacks being layered on top of one another.

-

It’s slow. To make sure you weren’t accidentally relying on stale libraries, you have your build script build every dependency in order every time you run it. You think about adding some logic to detect which parts need to be rebuilt, but that sounds awfully complex and error prone for a script. Or you think about specifying which parts need to be rebuilt each time, but then you’re back to square one.

-

Good news: it’s time for a release! Better go figure out all the arguments you need to pass to the

jarcommand to make your final build. And remember how to upload it and push it out to the central repository. And build and push the documentation updates, and send out a notification to users. Hmm, maybe this calls for another script... -

Disaster! Your hard drive crashes, and now you need to recreate your entire system. You were smart enough to keep all of your source files in version control, but what about those libraries you downloaded? Can you find them all again and make sure they were the same version as when you first downloaded them? Your scripts probably depended on particular tools being installed in particular places—can you restore that same environment so that the scripts work again? What about all those environment variables you set a long time ago to get the compiler working just right and then forgot about?

-

Despite the problems, your project is successful enough that you’re able to begin hiring more engineers. Now you realize that it doesn’t take a disaster for the previous problems to arise—you need to go through the same painful bootstrapping process every time a new developer joins your team. And despite your best efforts, there are still small differences in each person’s system. Frequently, what works on one person’s machine doesn’t work on another’s, and each time it takes a few hours of debugging tool paths or library versions to figure out where the difference is.

-

You decide that you need to automate your build system. In theory, this is as simple as getting a new computer and setting it up to run your build script every night using cron. You still need to go through the painful setup process, but now you don’t have the benefit of a human brain being able to detect and resolve minor problems. Now, every morning when you get in, you see that last night’s build failed because yesterday a developer made a change that worked on their system but didn’t work on the automated build system. Each time it’s a simple fix, but it happens so often that you end up spending a lot of time each day discovering and applying these simple fixes.

-

Builds become slower and slower as the project grows. One day, while waiting for a build to complete, you gaze mournfully at the idle desktop of your coworker, who is on vacation, and wish there were a way to take advantage of all that wasted computational power.

You’ve run into a classic problem of scale. For a single developer working on at most a couple hundred lines of code for at most a week or two (which might have been the entire experience thus far of a junior developer who just graduated university), a compiler is all you need. Scripts can maybe take you a little bit farther. But as soon as you need to coordinate across multiple developers and their machines, even a perfect build script isn’t enough because it becomes very difficult to account for the minor differences in those machines. At this point, this simple approach breaks down and it’s time to invest in a real build system.

Modern Build Systems

Fortunately, all of the problems we started running into have already been solved many times over by existing general-purpose build systems. Fundamentally, they aren’t that different from the aforementioned script-based DIY approach we were working on: they run the same compilers under the hood, and you need to understand those underlying tools to be able to know what the build system is really doing. But these existing systems have gone through many years of development, making them far more robust and flexible than the scripts you might try hacking together yourself.

It’s All About Dependencies

In looking through the previously described problems, one theme repeats over and over: managing your own code is fairly straightforward, but managing its dependencies is much more difficult (and Dependency Management is devoted to covering this problem in detail). There are all sorts of dependencies: sometimes there’s a dependency on a task (e.g., "push the documentation before I mark a release as complete"), and sometimes there’s a dependency on an artifact (e.g., "I need to have the latest version of the computer vision library to build my code"). Sometimes, you have internal dependencies on another part of your codebase, and sometimes you have external dependencies on code or data owned by another team (either in your organization or a third party). But in any case, the idea of "I need that before I can have this" is something that recurs repeatedly in the design of build systems, and managing dependencies is perhaps the most fundamental job of a build system.

Task-Based Build Systems

The shell scripts we started developing in the previous section were an example of a primitive task-based build system. In a task-based build system, the fundamental unit of work is the task. Each task is a script of some sort that can execute any sort of logic, and tasks specify other tasks as dependencies that must run before them. Most major build systems in use today, such as Ant, Maven, Gradle, Grunt, and Rake, are task based.

Instead of shell scripts, most modern build systems require engineers to create buildfiles that describe how to perform the build. Take this example from the Ant manual:

<project name="MyProject" default="dist" basedir=".">

<description>

simple example build file

</description>

<!-- set global properties for this build -->

<property name="src" location="src"/>

<property name="build" location="build"/>

<property name="dist" location="dist"/>

<target name="init">

<!-- Create the time stamp -->

<tstamp/>

<!-- Create the build directory structure used by compile -->

<mkdir dir="${build}"/>

</target>

<target name="compile" depends="init"

description="compile the source">

<!-- Compile the Java code from ${src} into ${build} -->

<javac srcdir="${src}" destdir="${build}"/>

</target>

<target name="dist" depends="compile"

description="generate the distribution">

<!-- Create the distribution directory -->

<mkdir dir="${dist}/lib"/>

<!-- Put everything in ${build} into the MyProject-${DSTAMP}.jar file -->

<jar jarfile="${dist}/lib/MyProject-${DSTAMP}.jar" basedir="${build}"/>

</target>

<target name="clean"

description="clean up">

<!-- Delete the ${build} and ${dist} directory trees -->

<delete dir="${build}"/>

<delete dir="${dist}"/>

</target>

</project>

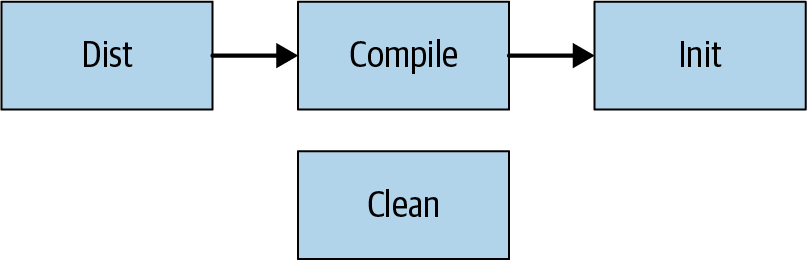

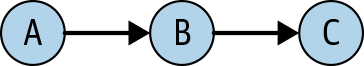

The buildfile is written in XML and defines some simple metadata about the build along with a list of tasks (the <target> tags in the XML3). Each task executes a list of possible commands defined by Ant, which here include creating and deleting directories, running javac, and creating a JAR file. This set of commands can be extended by user-provided plug-ins to cover any sort of logic. Each task can also define the tasks it depends on via the depends attribute. These dependencies form an acyclic graph (see Figure 18-1).

Users perform builds by providing tasks to Ant’s command-line tool. For example, when a user types ant dist, Ant takes the following steps:

-

Loads a file named build.xml in the current directory and parses it to create the graph structure shown in Figure 18-1.

-

Looks for the task named

distthat was provided on the command line and discovers that it has a dependency on the task namedcompile. -

Looks for the task named

compileand discovers that it has a dependency on the task namedinit. -

Looks for the task named

initand discovers that it has no dependencies. -

Executes the commands defined in the

inittask. -

Executes the commands defined in the

compiletask given that all of that task’s dependencies have been run. -

Executes the commands defined in the

disttask given that all of that task’s dependencies have been run.

In the end, the code executed by Ant when running the dist task is equivalent to the following shell script:

./createTimestamp.sh mkdir build/ javac src/* -d build/ mkdir -p dist/lib/ jar cf dist/lib/MyProject-$(date --iso-8601).jar build/*

When the syntax is stripped away, the buildfile and the build script actually aren’t too different. But we’ve already gained a lot by doing this. We can create new buildfiles in other directories and link them together. We can easily add new tasks that depend on existing tasks in arbitrary and complex ways. We need only pass the name of a single task to the ant command-line tool, and it will take care of determining everything that needs to be run.

Ant is a very old piece of software, originally released in 2000—not what many people would consider a "modern" build system today! Other tools like Maven and Gradle have improved on Ant in the intervening years and essentially replaced it by adding features like automatic management of external dependencies and a cleaner syntax without any XML. But the nature of these newer systems remains the same: they allow engineers to write build scripts in a principled and modular way as tasks and provide tools for executing those tasks and managing dependencies among them.

The dark side of task-based build systems

Because these tools essentially let engineers define any script as a task, they are extremely powerful, allowing you to do pretty much anything you can imagine with them. But that power comes with drawbacks, and task-based build systems can become difficult to work with as their build scripts grow more complex. The problem with such systems is that they actually end up giving too much power to engineers and not enough power to the system. Because the system has no idea what the scripts are doing, performance suffers, as it must be very conservative in how it schedules and executes build steps. And there’s no way for the system to confirm that each script is doing what it should, so scripts tend to grow in complexity and end up being another thing that needs debugging.

Difficulty of parallelizing build steps

Modern development workstations are typically quite powerful, with multiple cores that should theoretically be capable of executing several build steps in parallel. But task-based systems are often unable to parallelize task execution even when it seems like they should be able to. Suppose that task A depends on tasks B and C. Because tasks B and C have no dependency on each other, is it safe to run them at the same time so that the system can more quickly get to task A? Maybe, if they don’t touch any of the same resources. But maybe not—perhaps both use the same file to track their statuses and running them at the same time will cause a conflict. There’s no way in general for the system to know, so either it has to risk these conflicts (leading to rare but very difficult-to-debug build problems), or it has to restrict the entire build to running on a single thread in a single process. This can be a huge waste of a powerful developer machine, and it completely rules out the possibility of distributing the build across multiple machines.

Difficulty performing incremental builds

A good build system will allow engineers to perform reliable incremental builds such that a small change doesn’t require the entire codebase to be rebuilt from scratch. This is especially important if the build system is slow and unable to parallelize build steps for the aforementioned reasons. But unfortunately, task-based build systems struggle here, too. Because tasks can do anything, there’s no way in general to check whether they’ve already been done. Many tasks simply take a set of source files and run a compiler to create a set of binaries; thus, they don’t need to be rerun if the underlying source files haven’t changed. But without additional information, the system can’t say this for sure—maybe the task downloads a file that could have changed, or maybe it writes a timestamp that could be different on each run. To guarantee correctness, the system typically must rerun every task during each build.

Some build systems try to enable incremental builds by letting engineers specify the conditions under which a task needs to be rerun. Sometimes this is feasible, but often it’s a much trickier problem than it appears. For example, in languages like C++ that allow files to be included directly by other files, it’s impossible to determine the entire set of files that must be watched for changes without parsing the input sources. Engineers will often end up taking shortcuts, and these shortcuts can lead to rare and frustrating problems where a task result is reused even when it shouldn’t be. When this happens frequently, engineers get into the habit of running clean before every build to get a fresh state, completely defeating the purpose of having an incremental build in the first place. Figuring out when a task needs to be rerun is surprisingly subtle, and is a job better handled by machines than humans.

Difficulty maintaining and debugging scripts

Finally, the build scripts imposed by task-based build systems are often just difficult to work with. Though they often receive less scrutiny, build scripts are code just like the system being built, and are easy places for bugs to hide. Here are some examples of bugs that are very common when working with a task-based build system:

-

Task A depends on task B to produce a particular file as output. The owner of task B doesn’t realize that other tasks rely on it, so they change it to produce output in a different location. This can’t be detected until someone tries to run task A and finds that it fails.

-

Task A depends on task B, which depends on task C, which is producing a particular file as output that’s needed by task A. The owner of task B decides that it doesn’t need to depend on task C any more, which causes task A to fail even though task B doesn’t care about task C at all!

-

The developer of a new task accidentally makes an assumption about the machine running the task, such as the location of a tool or the value of particular environment variables. The task works on their machine, but fails whenever another developer tries it.

-

A task contains a nondeterministic component, such as downloading a file from the internet or adding a timestamp to a build. Now, people will get potentially different results each time they run the build, meaning that engineers won’t always be able to reproduce and fix one another’s failures or failures that occur on an automated build system.

-

Tasks with multiple dependencies can create race conditions. If task A depends on both task B and task C, and task B and C both modify the same file, task A will get a different result depending on which one of tasks B and C finishes first.

There’s no general-purpose way to solve these performance, correctness, or maintainability problems within the task-based framework laid out here. So long as engineers can write arbitrary code that runs during the build, the system can’t have enough information to always be able to run builds quickly and correctly. To solve the problem, we need to take some power out of the hands of engineers and put it back in the hands of the system and reconceptualize the role of the system not as running tasks, but as producing artifacts. This is the approach that Google takes with Blaze and Bazel, and it will be described in the next section.

Artifact-Based Build Systems

To design a better build system, we need to take a step back. The problem with the earlier systems is that they gave too much power to individual engineers by letting them define their own tasks. Maybe instead of letting engineers define tasks, we can have a small number of tasks defined by the system that engineers can configure in a limited way. We could probably deduce the name of the most important task from the name of this chapter: a build system’s primary task should be to build code. Engineers would still need to tell the system what to build, but the how of doing the build would be left to the system.

This is exactly the approach taken by Blaze and the other artifact-based build systems descended from it (which include Bazel, Pants, and Buck). Like with task-based build systems, we still have buildfiles, but the contents of those buildfiles are very different. Rather than being an imperative set of commands in a Turing-complete scripting language describing how to produce an output, buildfiles in Blaze are a declarative manifest describing a set of artifacts to build, their dependencies, and a limited set of options that affect how they’re built. When engineers run blaze on the command line, they specify a set of targets to build (the "what"), and Blaze is responsible for configuring, running, and scheduling the compilation steps (the "how"). Because the build system now has full control over what tools are being run when, it can make much stronger guarantees that allow it to be far more efficient while still guaranteeing correctness.

A functional perspective

It’s easy to make an analogy between artifact-based build systems and functional programming. Traditional imperative programming languages (e.g., Java, C, and Python) specify lists of statements to be executed one after another, in the same way that task-based build systems let programmers define a series of steps to execute. Functional programming languages (e.g., Haskell and ML), in contrast, are structured more like a series of mathematical equations. In functional languages, the programmer describes a computation to perform, but leaves the details of when and exactly how that computation is executed to the compiler. This maps to the idea of declaring a manifest in an artifact-based build system and letting the system figure out how to execute the build.

Many problems cannot be easily expressed using functional programming, but the ones that do benefit greatly from it: the language is often able to trivially parallelize such programs and make strong guarantees about their correctness that would be impossible in an imperative language. The easiest problems to express using functional programming are the ones that simply involve transforming one piece of data into another using a series of rules or functions. And that’s exactly what a build system is: the whole system is effectively a mathematical function that takes source files (and tools like the compiler) as inputs and produces binaries as outputs. So, it’s not surprising that it works well to base a build system around the tenets of functional programming.

Getting concrete with Bazel

Bazel is the open source version of Google’s internal build tool, Blaze, and is a good example of an artifact-based build system. Here’s what a buildfile (normally named BUILD) looks like in Bazel:

java_binary(

name = "MyBinary",

srcs = ["MyBinary.java"],

deps = [

":mylib",

],

)

java_library(

name = "mylib",

srcs = ["MyLibrary.java", "MyHelper.java"],

visibility = ["//java/com/example/myproduct:__subpackages__"],

deps = [

"//java/com/example/common",

"//java/com/example/myproduct/otherlib",

"@com_google_common_guava_guava//jar",

],

)

In Bazel, BUILD files define targets—the two types of targets here are java_binary and java_library. Every target corresponds to an artifact that can be created by the system: binary targets produce binaries that can be executed directly, and library targets produce libraries that can be used by binaries or other libraries. Every target has a name (which defines how it is referenced on the command line and by other targets), srcs (which define the source files that must be compiled to create the artifact for the target), and deps (which define other targets that must be built before this target and linked into it). Dependencies can either be within the same package (e.g., MyBinary’s dependency on ":mylib"), on a different package in the same source hierarchy (e.g., mylib’s dependency on "//java/com/example/common"), or on a third-party artifact outside of the source hierarchy (e.g., mylib’s dependency on "@com_google_common_guava_guava//jar"). Each source hierarchy is called a workspace and is identified by the presence of a special WORKSPACE file at the root.

Like with Ant, users perform builds using Bazel’s command-line tool. To build the MyBinary target, a user would run bazel build :MyBinary. Upon entering that command for the first time in a clean repository, Bazel would do the following:

-

Parse every BUILD file in the workspace to create a graph of dependencies among artifacts.

-

Use the graph to determine the transitive dependencies of

MyBinary;that is, every target thatMyBinarydepends on and every target that those targets depend on, recursively. -

Build (or download for external dependencies) each of those dependencies, in order. Bazel starts by building each target that has no other dependencies and keeps track of which dependencies still need to be built for each target. As soon as all of a target’s dependencies are built, Bazel starts building that target. This process continues until every one of

MyBinary’s transitive dependencies have been built. -

Build

MyBinaryto produce a final executable binary that links in all of the dependencies that were built in step 3.

Fundamentally, it might not seem like what’s happening here is that much different than what happened when using a task-based build system. Indeed, the end result is the same binary, and the process for producing it involved analyzing a bunch of steps to find dependencies among them, and then running those steps in order. But there are critical differences. The first one appears in step 3: because Bazel knows that each target will only produce a Java library, it knows that all it has to do is run the Java compiler rather than an arbitrary user-defined script, so it knows that it’s safe to run these steps in parallel. This can produce an order of magnitude performance improvement over building targets one at a time on a multicore machine, and is only possible because the artifact-based approach leaves the build system in charge of its own execution strategy so that it can make stronger guarantees about parallelism.

The benefits extend beyond parallelism, though. The next thing that this approach gives us becomes apparent when the developer types bazel build :MyBinary a second time without making any changes: Bazel will exit in less than a second with a message saying that the target is up to date. This is possible due to the functional programming paradigm we talked about earlier—Bazel knows that each target is the result only of running a Java compiler, and it knows that the output from the Java compiler depends only on its inputs, so as long as the inputs haven’t changed, the output can be reused. And this analysis works at every level; if MyBinary.java changes, Bazel knows to rebuild MyBinary but reuse mylib. If a source file for //java/com/example/common changes, Bazel knows to rebuild that library, mylib, and MyBinary, but reuse //java/com/example/myproduct/otherlib. Because Bazel knows about the properties of the tools it runs at every step, it’s able to rebuild only the minimum set of artifacts each time while guaranteeing that it won’t produce stale builds.

Reframing the build process in terms of artifacts rather than tasks is subtle but powerful. By reducing the flexibility exposed to the programmer, the build system can know more about what is being done at every step of the build. It can use this knowledge to make the build far more efficient by parallelizing build processes and reusing their outputs. But this is really just the first step, and these building blocks of parallelism and reuse will form the basis for a distributed and highly scalable build system that will be discussed later.

Other nifty Bazel tricks

Artifact-based build systems fundamentally solve the problems with parallelism and reuse that are inherent in task-based build systems. But there are still a few problems that came up earlier that we haven’t addressed. Bazel has clever ways of solving each of these, and we should discuss them before moving on.

Tools as dependencies

One problem we ran into earlier was that builds depended on the tools installed on our machine, and reproducing builds across systems could be difficult due to different tool versions or locations. The problem becomes even more difficult when your project uses languages that require different tools based on which platform they’re being built on or compiled for (e.g., Windows versus Linux), and each of those platforms requires a slightly different set of tools to do the same job.

Bazel solves the first part of this problem by treating tools as dependencies to each target. Every java_library in the workspace implicitly depends on a Java compiler, which defaults to a well-known compiler but can be configured globally at the workspace level. Whenever Blaze builds a java_library, it checks to make sure that the specified compiler is available at a known location and downloads it if not. Just like any other dependency, if the Java compiler changes, every artifact that was dependent upon it will need to be rebuilt. Every type of target defined in Bazel uses this same strategy of declaring the tools it needs to run, ensuring that Bazel is able to bootstrap them no matter what exists on the system where it runs.

Bazel solves the second part of the problem, platform independence, by using toolchains. Rather than having targets depend directly on their tools, they actually depend on types of toolchains. A toolchain contains a set of tools and other properties defining how a type of target is built on a particular platform. The workspace can define the particular toolchain to use for a toolchain type based on the host and target platform. For more details, see the Bazel manual.

Extending the build system

Bazel comes with targets for several popular programming languages out of the box, but engineers will always want to do more—part of the benefit of task-based systems is their flexibility in supporting any kind of build process, and it would be better not to give that up in an artifact-based build system. Fortunately, Bazel allows its supported target types to be extended by adding custom rules.

To define a rule in Bazel, the rule author declares the inputs that the rule requires (in the form of attributes passed in the BUILD file) and the fixed set of outputs that the rule produces. The author also defines the actions that will be generated by that rule. Each action declares its inputs and outputs, runs a particular executable or writes a particular string to a file, and can be connected to other actions via its inputs and outputs. This means that actions are the lowest-level composable unit in the build system—an action can do whatever it wants so long as it uses only its declared inputs and outputs, and Bazel will take care of scheduling actions and caching their results as appropriate.

The system isn’t foolproof given that there’s no way to stop an action developer from doing something like introducing a nondeterministic process as part of their action. But this doesn’t happen very often in practice, and pushing the possibilities for abuse all the way down to the action level greatly decreases opportunities for errors. Rules supporting many common languages and tools are widely available online, and most projects will never need to define their own rules. Even for those that do, rule definitions only need to be defined in one central place in the repository, meaning most engineers will be able to use those rules without ever having to worry about their implementation.

Isolating the environment

Actions sound like they might run into the same problems as tasks in other systems—isn’t it still possible to write actions that both write to the same file and end up conflicting with one another? Actually, Bazel makes these conflicts impossible by using sandboxing. On supported systems, every action is isolated from every other action via a filesystem sandbox. Effectively, each action can see only a restricted view of the filesystem that includes the inputs it has declared and any outputs it has produced. This is enforced by systems such as LXC on Linux, the same technology behind Docker. This means that it’s impossible for actions to conflict with one another because they are unable to read any files they don’t declare, and any files that they write but don’t declare will be thrown away when the action finishes. Bazel also uses sandboxes to restrict actions from communicating via the network.

Making external dependencies deterministic

There’s still one problem remaining: build systems often need to download dependencies (whether tools or libraries) from external sources rather than directly building them. This can be seen in the example via the @com_google_common_guava_guava//jar dependency, which downloads a JAR file from Maven.

Depending on files outside of the current workspace is risky. Those files could change at any time, potentially requiring the build system to constantly check whether they’re fresh. If a remote file changes without a corresponding change in the workspace source code, it can also lead to unreproducible builds—a build might work one day and fail the next for no obvious reason due to an unnoticed dependency change. Finally, an external dependency can introduce a huge security risk when it is owned by a third party:4 if an attacker is able to infiltrate that third-party server, they can replace the dependency file with something of their own design, potentially giving them full control over your build environment and its output.

The fundamental problem is that we want the build system to be aware of these files without having to check them into source control. Updating a dependency should be a conscious choice, but that choice should be made once in a central place rather than managed by individual engineers or automatically by the system. This is because even with a "Live at Head" model, we still want builds to be deterministic, which implies that if you check out a commit from last week, you should see your dependencies as they were then rather than as they are now.

Bazel and some other build systems address this problem by requiring a workspace-wide manifest file that lists a cryptographic hash for every external dependency in the workspace.5 The hash is a concise way to uniquely represent the file without checking the entire file into source control. Whenever a new external dependency is referenced from a workspace, that dependency’s hash is added to the manifest, either manually or automatically. When Bazel runs a build, it checks the actual hash of its cached dependency against the expected hash defined in the manifest and redownloads the file only if the hash differs.

If the artifact we download has a different hash than the one declared in the manifest, the build will fail unless the hash in the manifest is updated. This can be done automatically, but that change must be approved and checked into source control before the build will accept the new dependency. This means that there’s always a record of when a dependency was updated, and an external dependency can’t change without a corresponding change in the workspace source. It also means that, when checking out an older version of the source code, the build is guaranteed to use the same dependencies that it was using at the point when that version was checked in (or else it will fail if those dependencies are no longer available).

Of course, it can still be a problem if a remote server becomes unavailable or starts serving corrupt data—this can cause all of your builds to begin failing if you don’t have another copy of that dependency available. To avoid this problem, we recommend that, for any nontrivial project, you mirror all of its dependencies onto servers or services that you trust and control. Otherwise you will always be at the mercy of a third party for your build system’s availability, even if the checked-in hashes guarantee its security.

Distributed Builds

Google’s codebase is enormous—with more than two billion lines of code, chains of dependencies can become very deep. Even simple binaries at Google often depend on tens of thousands of build targets. At this scale, it’s simply impossible to complete a build in a reasonable amount of time on a single machine: no build system can get around the fundamental laws of physics imposed on a machine’s hardware. The only way to make this work is with a build system that supports distributed builds wherein the units of work being done by the system are spread across an arbitrary and scalable number of machines. Assuming we’ve broken the system’s work into small enough units (more on this later), this would allow us to complete any build of any size as quickly as we’re willing to pay for. This scalability is the holy grail we’ve been working toward by defining an artifact-based build system.

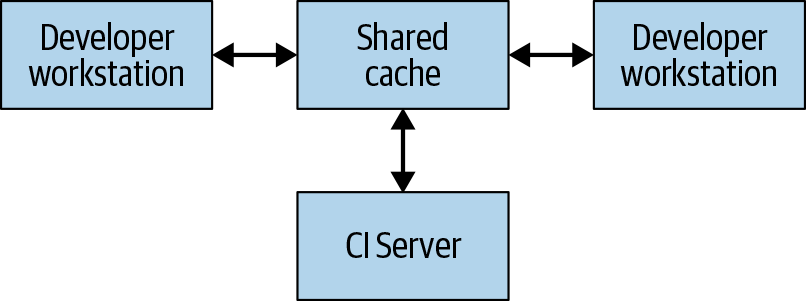

Remote caching

The simplest type of distributed build is one that only leverages remote caching, which is shown in Figure 18-2.

Every system that performs builds, including both developer workstations and continuous integration systems, shares a reference to a common remote cache service. This service might be a fast and local short-term storage system like Redis or a cloud service like Google Cloud Storage. Whenever a user needs to build an artifact, whether directly or as a dependency, the system first checks with the remote cache to see if that artifact already exists there. If so, it can download the artifact instead of building it. If not, the system builds the artifact itself and uploads the result back to the cache. This means that low-level dependencies that don’t change very often can be built once and shared across users rather than having to be rebuilt by each user. At Google, many artifacts are served from a cache rather than built from scratch, vastly reducing the cost of running our build system.

For a remote caching system to work, the build system must guarantee that builds are completely reproducible. That is, for any build target, it must be possible to determine the set of inputs to that target such that the same set of inputs will produce exactly the same output on any machine. This is the only way to ensure that the results of downloading an artifact are the same as the results of building it oneself. Fortunately, Bazel provides this guarantee and so supports remote caching. Note that this requires that each artifact in the cache be keyed on both its target and a hash of its inputs—that way, different engineers could make different modifications to the same target at the same time, and the remote cache would store all of the resulting artifacts and serve them appropriately without conflict.

Of course, for there to be any benefit from a remote cache, downloading an artifact needs to be faster than building it. This is not always the case, especially if the cache server is far from the machine doing the build. Google’s network and build system is carefully tuned to be able to quickly share build results. When configuring remote caching in your organization, take care to consider network latencies and perform experiments to ensure that the cache is actually improving performance.

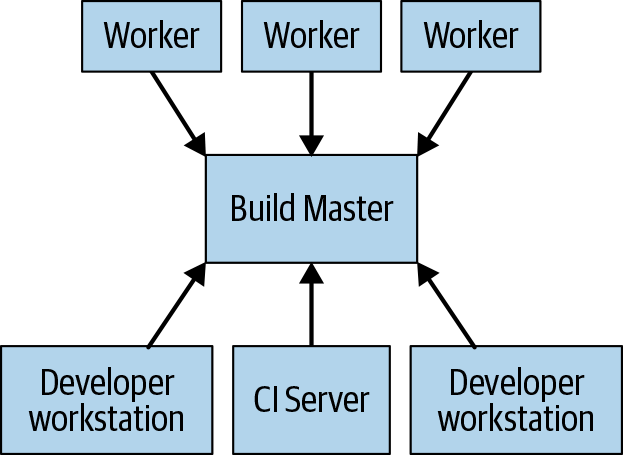

Remote execution

Remote caching isn’t a true distributed build. If the cache is lost or if you make a low-level change that requires everything to be rebuilt, you still need to perform the entire build locally on your machine. The true goal is to support remote execution, in which the actual work of doing the build can be spread across any number of workers. Figure 18-3 depicts a remote execution system.

The build tool running on each user’s machine (where users are either human engineers or automated build systems) sends requests to a central build master. The build master breaks the requests into their component actions and schedules the execution of those actions over a scalable pool of workers. Each worker performs the actions asked of it with the inputs specified by the user and writes out the resulting artifacts. These artifacts are shared across the other machines executing actions that require them until the final output can be produced and sent to the user.

The trickiest part of implementing such a system is managing the communication between the workers, the master, and the user’s local machine. Workers might depend on intermediate artifacts produced by other workers, and the final output needs to be sent back to the user’s local machine. To do this, we can build on top of the distributed cache described previously by having each worker write its results to and read its dependencies from the cache. The master blocks workers from proceeding until everything they depend on has finished, in which case they’ll be able to read their inputs from the cache. The final product is also cached, allowing the local machine to download it. Note that we also need a separate means of exporting the local changes in the user’s source tree so that workers can apply those changes before building.

For this to work, all of the parts of the artifact-based build systems described earlier need to come together. Build environments must be completely self-describing so that we can spin up workers without human intervention. Build processes themselves must be completely self-contained because each step might be executed on a different machine. Outputs must be completely deterministic so that each worker can trust the results it receives from other workers. Such guarantees are extremely difficult for a task-based system to provide, which makes it nigh-impossible to build a reliable remote execution system on top of one.

Distributed builds at Google

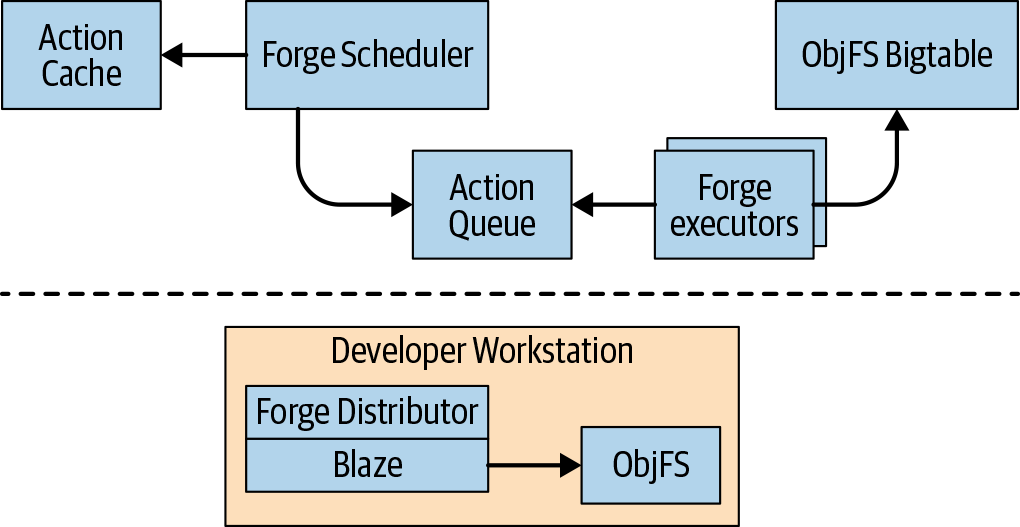

Since 2008, Google has been using a distributed build system that employs both remote caching and remote execution, which is illustrated in Figure 18-4.

Google’s remote cache is called ObjFS. It consists of a backend that stores build outputs in Bigtables distributed throughout our fleet of production machines and a frontend FUSE daemon named objfsd that runs on each developer’s machine. The FUSE daemon allows engineers to browse build outputs as if they were normal files stored on the workstation, but with the file content downloaded on-demand only for the few files that are directly requested by the user. Serving file contents on-demand greatly reduces both network and disk usage, and the system is able to build twice as fast compared to when we stored all build output on the developer’s local disk.

Google’s remote execution system is called Forge. A Forge client in Blaze called the Distributor sends requests for each action to a job running in our datacenters called the Scheduler. The Scheduler maintains a cache of action results, allowing it to return a response immediately if the action has already been created by any other user of the system. If not, it places the action into a queue. A large pool of Executor jobs continually read actions from this queue, execute them, and store the results directly in the ObjFS Bigtables. These results are available to the executors for future actions, or to be downloaded by the end user via objfsd.

The end result is a system that scales to efficiently support all builds performed at Google. And the scale of Google’s builds is truly massive: Google runs millions of builds executing millions of test cases and producing petabytes of build outputs from billions of lines of source code every day. Not only does such a system let our engineers build complex codebases quickly, it also allows us to implement a huge number of automated tools and systems that rely on our build. We put many years of effort into developing this system, but nowadays open source tools are readily available such that any organization can implement a similar system. Though it can take time and energy to deploy such a build system, the end result can be truly magical for engineers and is often well worth the effort.

Time, Scale, Trade-Offs

Build systems are all about making code easier to work with at scale and over time. And like everything in software engineering, there are trade-offs in choosing which sort of build system to use. The DIY approach using shell scripts or direct invocations of tools works only for the smallest projects that don’t need to deal with code changing over a long period of time, or for languages like Go that have a built-in build system.

Choosing a task-based build system instead of relying on DIY scripts greatly improves your project’s ability to scale, allowing you to automate complex builds and more easily reproduce those builds across machines. The trade-off is that you need to actually start putting some thought into how your build is structured and deal with the overhead of writing build files (though automated tools can often help with this). This trade-off tends to be worth it for most projects, but for particularly trivial projects (e.g., those contained in a single source file), the overhead might not buy you much.

Task-based build systems begin to run into some fundamental problems as the project scales further, and these issues can be remedied by using an artifact-based build system instead. Such build systems unlock a whole new level of scale because huge builds can now be distributed across many machines, and thousands of engineers can be more certain that their builds are consistent and reproducible. As with so many other topics in this book, the trade-off here is a lack of flexibility: artifact-based systems don’t let you write generic tasks in a real programming language, but require you to work within the constraints of the system. This is usually not a problem for projects that are designed to work with artifact-based systems from the start, but migration from an existing task-based system can be difficult and is not always worth it if the build isn’t already showing problems in terms of speed or correctness.

Changes to a project’s build system can be expensive, and that cost increases as the project becomes larger. This is why Google believes that almost every new project benefits from incorporating an artifact-based build system like Bazel right from the start. Within Google, essentially all code from tiny experimental projects up to Google Search is built using Blaze.

Dealing with Modules and Dependencies

Projects that use artifact-based build systems like Bazel are broken into a set of modules, with modules expressing dependencies on one another via BUILD files. Proper organization of these modules and dependencies can have a huge effect on both the performance of the build system and how much work it takes to maintain.

Using Fine-Grained Modules and the 1:1:1 Rule

The first question that comes up when structuring an artifact-based build is deciding how much functionality an individual module should encompass. In Bazel, a "module" is represented by a target specifying a buildable unit like a java_library or a go_binary. At one extreme, the entire project could be contained in a single module by putting one BUILD file at the root and recursively globbing together all of that project’s source files. At the other extreme, nearly every source file could be made into its own module, effectively requiring each file to list in a BUILD file every other file it depends on.

Most projects fall somewhere between these extremes, and the choice involves a trade-off between performance and maintainability. Using a single module for the entire project might mean that you never need to touch the BUILD file except when adding an external dependency, but it means that the build system will always need to build the entire project all at once. This means that it won’t be able to parallelize or distribute parts of the build, nor will it be able to cache parts that it’s already built. One-module-per-file is the opposite: the build system has the maximum flexibility in caching and scheduling steps of the build, but engineers need to expend more effort maintaining lists of dependencies whenever they change which files reference which.

Though the exact granularity varies by language (and often even within language), Google tends to favor significantly smaller modules than one might typically write in a task-based build system. A typical production binary at Google will likely depend on tens of thousands of targets, and even a moderate-sized team can own several hundred targets within its codebase. For languages like Java that have a strong built-in notion of packaging, each directory usually contains a single package, target, and BUILD file (Pants, another build system based on Blaze, calls this the 1:1:1 rule). Languages with weaker packaging conventions will frequently define multiple targets per BUILD file.

The benefits of smaller build targets really begin to show at scale because they lead to faster distributed builds and a less frequent need to rebuild targets. The advantages become even more compelling after testing enters the picture, as finer-grained targets mean that the build system can be much smarter about running only a limited subset of tests that could be affected by any given change. Because Google believes in the systemic benefits of using smaller targets, we’ve made some strides in mitigating the downside by investing in tooling to automatically manage BUILD files to avoid burdening developers. Many of these tools are now open source.

Minimizing Module Visibility

Bazel and other build systems allow each target to specify a visibility: a property that specifies which other targets may depend on it. Targets can be public, in which case they can be referenced by any other target in the workspace; private, in which case they can be referenced only from within the same BUILD file; or visible to only an explicitly defined list of other targets. A visibility is essentially the opposite of a dependency: if target A wants to depend on target B, target B must make itself visible to target A.

Just like in most programming languages, it is usually best to minimize visibility as much as possible. Generally, teams at Google will make targets public only if those targets represent widely used libraries available to any team at Google. Teams that require others to coordinate with them before using their code will maintain a whitelist of customer targets as their target’s visibility. Each team’s internal implementation targets will be restricted to only directories owned by the team, and most BUILD files will have only one target that isn’t private.

Managing Dependencies

Modules need to be able to refer to one another. The downside of breaking a codebase into fine-grained modules is that you need to manage the dependencies among those modules (though tools can help automate this). Expressing these dependencies usually ends up being the bulk of the content in a BUILD file.

Internal dependencies

In a large project broken into fine-grained modules, most dependencies are likely to be internal; that is, on another target defined and built in the same source repository. Internal dependencies differ from external dependencies in that they are built from source rather than downloaded as a prebuilt artifact while running the build. This also means that there’s no notion of "version" for internal dependencies—a target and all of its internal dependencies are always built at the same commit/revision in the repository.

One issue that should be handled carefully with regard to internal dependencies is how to treat transitive dependencies (Figure 18-5). Suppose target A depends on target B, which depends on a common library target C. Should target A be able to use classes defined in target C?

As far as the underlying tools are concerned, there’s no problem with this; both B and C will be linked into target A when it is built, so any symbols defined in C are known to A. Blaze allowed this for many years, but as Google grew, we began to see problems. Suppose that B was refactored such that it no longer needed to depend on C. If B’s dependency on C was then removed, A and any other target that used C via a dependency on B would break. Effectively, a target’s dependencies became part of its public contract and could never be safely changed. This meant that dependencies accumulated over time and builds at Google started to slow down.

Google eventually solved this issue by introducing a "strict transitive dependency mode" in Blaze. In this mode, Blaze detects whether a target tries to reference a symbol without depending on it directly and, if so, fails with an error and a shell command that can be used to automatically insert the dependency. Rolling this change out across Google’s entire codebase and refactoring every one of our millions of build targets to explicitly list their dependencies was a multiyear effort, but it was well worth it. Our builds are now much faster given that targets have fewer unnecessary dependencies,6 and engineers are empowered to remove dependencies they don’t need without worrying about breaking targets that depend on them.

As usual, enforcing strict transitive dependencies involved a trade-off. It made build files more verbose, as frequently used libraries now need to be listed explicitly in many places rather than pulled in incidentally, and engineers needed to spend more effort adding dependencies to BUILD files. We’ve since developed tools that reduce this toil by automatically detecting many missing dependencies and adding them to a BUILD files without any developer intervention. But even without such tools, we’ve found the trade-off to be well worth it as the codebase scales: explicitly adding a dependency to BUILD file is a one-time cost, but dealing with implicit transitive dependencies can cause ongoing problems as long as the build target exists. Bazel enforces strict transitive dependencies on Java code by default.

External dependencies

If a dependency isn’t internal, it must be external. External dependencies are those on artifacts that are built and stored outside of the build system. The dependency is imported directly from an artifact repository (typically accessed over the internet) and used as-is rather than being built from source. One of the biggest differences between external and internal dependencies is that external dependencies have versions, and those versions exist independently of the project’s source code.

Automatic versus manual dependency management

Build systems can allow the versions of external dependencies to be managed either manually or automatically. When managed manually, the buildfile explicitly lists the version it wants to download from the artifact repository, often using a semantic version string such as "1.1.4". When managed automatically, the source file specifies a range of acceptable versions, and the build system always downloads the latest one. For example, Gradle allows a dependency version to be declared as "1.+" to specify that any minor or patch version of a dependency is acceptable so long as the major version is 1.

Automatically managed dependencies can be convenient for small projects, but they’re usually a recipe for disaster on projects of nontrivial size or that are being worked on by more than one engineer. The problem with automatically managed dependencies is that you have no control over when the version is updated. There’s no way to guarantee that external parties won’t make breaking updates (even when they claim to use semantic versioning), so a build that worked one day might be broken the next with no easy way to detect what changed or to roll it back to a working state. Even if the build doesn’t break, there can be subtle behavior or performance changes that are impossible to track down.

In contrast, because manually managed dependencies require a change in source control, they can be easily discovered and rolled back, and it’s possible to check out an older version of the repository to build with older dependencies. Bazel requires that versions of all dependencies be specified manually. At even moderate scales, the overhead of manual version management is well worth it for the stability it provides.

The One-Version Rule

Different versions of a library are usually represented by different artifacts, so in theory there’s no reason that different versions of the same external dependency couldn’t both be declared in the build system under different names. That way, each target could choose which version of the dependency it wanted to use. Google has found this to cause a lot of problems in practice, so we enforce a strict One-Version Rule for all third-party dependencies in our internal codebase.

The biggest problem with allowing multiple versions is the diamond dependency issue. Suppose that target A depends on target B and on v1 of an external library. If target B is later refactored to add a dependency on v2 of the same external library, target A will break because it now depends implicitly on two different versions of the same library. Effectively, it’s never safe to add a new dependency from a target to any third-party library with multiple versions, because any of that target’s users could already be depending on a different version. Following the One-Version Rule makes this conflict impossible—if a target adds a dependency on a third-party library, any existing dependencies will already be on that same version, so they can happily coexist.

We’ll examine this further in the context of a large monorepo in Dependency Management.

Transitive external dependencies

Dealing with the transitive dependencies of an external dependency can be particularly difficult. Many artifact repositories such as Maven Central allow artifacts to specify dependencies on particular versions of other artifacts in the repository. Build tools like Maven or Gradle will often recursively download each transitive dependency by default, meaning that adding a single dependency in your project could potentially cause dozens of artifacts to be downloaded in total.

This is very convenient: when adding a dependency on a new library, it would be a big pain to have to track down each of that library’s transitive dependencies and add them all manually. But there’s also a huge downside: because different libraries can depend on different versions of the same third-party library, this strategy necessarily violates the One-Version Rule and leads to the diamond dependency problem. If your target depends on two external libraries that use different versions of the same dependency, there’s no telling which one you’ll get. This also means that updating an external dependency could cause seemingly unrelated failures throughout the codebase if the new version begins pulling in conflicting versions of some of its dependencies.

For this reason, Bazel does not automatically download transitive dependencies. And, unfortunately, there’s no silver bullet—Bazel’s alternative is to require a global file that lists every single one of the repository’s external dependencies and an explicit version used for that dependency throughout the repository. Fortunately, Bazel provides tools that are able to automatically generate such a file containing the transitive dependencies of a set of Maven artifacts. This tool can be run once to generate the initial WORKSPACE file for a project, and that file can then be manually updated to adjust the versions of each dependency.

Yet again, the choice here is one between convenience and scalability. Small projects might prefer not having to worry about managing transitive dependencies themselves and might be able to get away with using automatic transitive dependencies. This strategy becomes less and less appealing as the organization and codebase grows, and conflicts and unexpected results become more and more frequent. At larger scales, the cost of manually managing dependencies is much less than the cost of dealing with issues caused by automatic dependency management.

Caching build results using external dependencies

External dependencies are most often provided by third parties that release stable versions of libraries, perhaps without providing source code. Some organizations might also choose to make some of their own code available as artifacts, allowing other pieces of code to depend on them as third-party rather than internal dependencies. This can theoretically speed up builds if artifacts are slow to build but quick to download.

However, this also introduces a lot of overhead and complexity: someone needs to be responsible for building each of those artifacts and uploading them to the artifact repository, and clients need to ensure that they stay up to date with the latest version. Debugging also becomes much more difficult because different parts of the system will have been built from different points in the repository, and there is no longer a consistent view of the source tree.

A better way to solve the problem of artifacts taking a long time to build is to use a build system that supports remote caching, as described earlier. Such a build system will save the resulting artifacts from every build to a location that is shared across engineers, so if a developer depends on an artifact that was recently built by someone else, the build system will automatically download it instead of building it. This provides all of the performance benefits of depending directly on artifacts while still ensuring that builds are as consistent as if they were always built from the same source. This is the strategy used internally by Google, and Bazel can be configured to use a remote cache.

Security and reliability of external dependencies

Depending on artifacts from third-party sources is inherently risky. There’s an availability risk if the third-party source (e.g., an artifact repository) goes down, because your entire build might grind to a halt if it’s unable to download an external dependency. There’s also a security risk: if the third-party system is compromised by an attacker, the attacker could replace the referenced artifact with one of their own design, allowing them to inject arbitrary code into your build.

Both problems can be mitigated by mirroring any artifacts you depend on onto servers you control and blocking your build system from accessing third-party artifact repositories like Maven Central. The trade-off is that these mirrors take effort and resources to maintain, so the choice of whether to use them often depends on the scale of the project. The security issue can also be completely prevented with little overhead by requiring the hash of each third-party artifact to be specified in the source repository, causing the build to fail if the artifact is tampered with.

Another alternative that completely sidesteps the issue is to vendor your project’s dependencies. When a project vendors its dependencies, it checks them into source control alongside the project’s source code, either as source or as binaries. This effectively means that all of the project’s external dependencies are converted to internal dependencies. Google uses this approach internally, checking every third-party library referenced throughout Google into a third_party directory at the root of Google’s source tree. However, this works at Google only because Google’s source control system is custom built to handle an extremely large monorepo, so vendoring might not be an option for other organizations.

Conclusion

A build system is one of the most important parts of an engineering organization. Each developer will interact with it potentially dozens or hundreds of times per day, and in many situations, it can be the rate-limiting step in determining their productivity. This means that it’s worth investing time and thought into getting things right.

As discussed in this chapter, one of the more surprising lessons that Google has learned is that limiting engineers’ power and flexibility can improve their productivity. We were able to develop a build system that meets our needs not by giving engineers free reign in defining how builds are performed, but by developing a highly structured framework that limits individual choice and leaves most interesting decisions in the hands of automated tools. And despite what you might think, engineers don’t resent this: Googlers love that this system mostly works on its own and lets them focus on the interesting parts of writing their applications instead of grappling with build logic. Being able to trust the build is powerful—incremental builds just work, and there is almost never a need to clear build caches or run a “clean” step.

We took this insight and used it to create a whole new type of artifact-based build system, contrasting with traditional task-based build systems. This reframing of the build as centering around artifacts instead of tasks is what allows our builds to scale to an organization the size of Google. At the extreme end, it allows for a distributed build system that is able to leverage the resources of an entire compute cluster to accelerate engineers’ productivity. Though your organization might not be large enough to benefit from such an investment, we believe that artifact-based build systems scale down as well as they scale up: even for small projects, build systems like Bazel can bring significant benefits in terms of speed and correctness.

The remainder of this chapter explored how to manage dependencies in an artifact-based world. We came to the conclusion that fine-grained modules scale better than coarse-grained modules. We also discussed the difficulties of managing dependency versions, describing the One-Version Rule and the observation that all dependencies should be versioned manually and explicitly. Such practices avoid common pitfalls like the diamond dependency issue and allow a codebase to achieve Google’s scale of billions of lines of code in a single repository with a unified build system.

TL;DRs

-

A fully featured build system is necessary to keep developers productive as an organization scales.

-

Power and flexibility come at a cost. Restricting the build system appropriately makes it easier on developers.

-

Build systems organized around artifacts tend to scale better and be more reliable than build systems organized around tasks.

-

When defining artifacts and dependencies, it’s better to aim for fine-grained modules. Fine-grained modules are better able to take advantage of parallelism and incremental builds.

-

External dependencies should be versioned explicitly under source control. Relying on "latest" versions is a recipe for disaster and unreproducible builds.

1In an internal survey, 83% of Googlers reported being satisfied with the build system, making it the fourth most satisfying tool of the 19 surveyed. The average tool had a satisfaction rating of 69%.

2See https://buck.build/ and https://www.pantsbuild.org/index.html.

3Ant uses the word "target" to represent what we call a "task" in this chapter, and it uses the word "task" to refer to what we call "commands."

4Such "software supply chain" attacks are becoming more common.

5Go recently added preliminary support for modules using the exact same system.

6Of course, actually removing these dependencies was a whole separate process. But requiring each target to explicitly declare what it used was a critical first step. See Large-Scale Changes for more information about how Google makes large-scale changes like this.