Code Search

Code Search is a tool for browsing and searching code at Google that consists of a frontend UI and various backend elements. Like many of the development tools at Google, it arose directly out of a need to scale to the size of the codebase. Code Search began as a combination of a grep-type tool1 for internal code with the ranking and UI of external Code Search.2 Its place as a key tool for Google developers was cemented by the integration of Kythe/Grok,3 which added cross-references and the ability to jump to symbol definitions.

That integration changed its focus from searching to browsing code, and later development of Code Search was partly guided by a principle of "answering the next question about code in a single click." Now such questions as "Where is this symbol defined?", "Where is it used?", "How do I include it?", "When was it added to the codebase?", and even ones like "Fleet-wide, how many CPU cycles does it consume?" are all answerable with one or two clicks.

In contrast to integrated development environments (IDEs) or code editors, Code Search is optimized for the use case of reading, understanding, and exploring code at scale. To do so, it relies heavily on cloud-based backends for searching content and resolving cross-references.

In this chapter, we’ll look at Code Search in more detail, including how Googlers use it as part of their developer workflows, why we chose to develop a separate web tool for code searching, and examine how it addresses the challenges of searching and browsing code at Google repository scale.

The Code Search UI

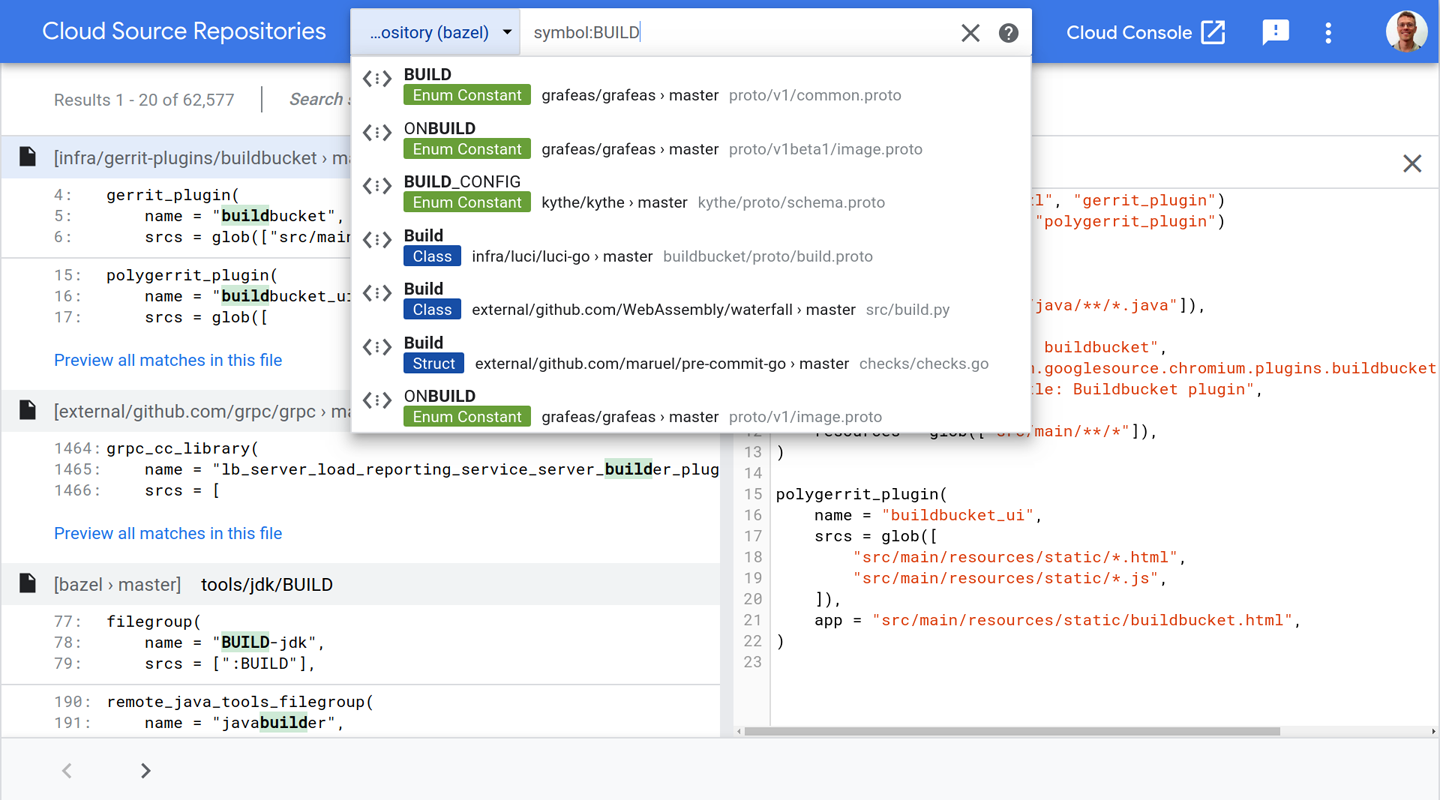

The search box is a central element of the Code Search UI (see Figure 17-1), and like web search, it has "suggestions" that developers can use for quick navigation to files, symbols, or directories. For more complex use cases, a results page with code snippets is returned. The search itself can be thought of as an instant “find in files” (like the Unix grep command) with relevance ranking and some code-specific enhancements like proper syntax highlighting, scope awareness, and awareness of comments and string literals. Search is also available from the command line and can be incorporated into other tools via a Remote Procedure Call (RPC) API. This comes in handy when post-processing is required or if the result set is too large for manual inspection.

When viewing a single file, most tokens are clickable to let the user quickly navigate to related information. For example, a function call will link to its function definition, an imported filename to the actual source file, or a bug ID in a comment to the corresponding bug report. This is powered by compiler-based indexing tools like Kythe. Clicking the symbol name opens a panel with all the places the symbol is used. Similarly, hovering over local variables in a function will highlight all occurrences of that variable in the implementation.

Code Search also shows the history of a file, via its integration with Piper (see Version Control and Branch Management). This means seeing older versions of the file, which changes have affected it, who wrote them, jumping to them in Critique (see Critique: Google’s Code Review Tool), diffing versions of files, and the classic "blame" view if desired. Even deleted files can be seen from a directory view.

How Do Googlers Use Code Search?

Although similar functionality is available in other tools, Googlers still make heavy use of the Code Search UI for searching and file viewing and ultimately for understanding code.4 The tasks engineers try to complete with Code Search can be thought of answering questions about code, and recurring intents become visible.5

Where?

About 16% of Code Searches try to answer the question of where a specific piece of information exists in the codebase; for example, a function definition or configuration, all usages of an API, or just where a specific file is in the repository. These questions are very targeted and can be very precisely answered with either search queries or by following semantic links, like "jump to symbol definition." Such questions often arise during larger tasks like refactorings/cleanups or when collaborating with other engineers on a project. Therefore, it is essential that these small knowledge gaps are addressed efficiently.

Code Search provides two ways of helping: ranking the results, and a rich query language. Ranking addresses the common cases, and searches can be made very specific (e.g., restricting code paths, excluding languages, only considering functions) to deal with rarer cases.

The UI makes it easy to share a Code Search result with colleagues. So, for code reviews, you can simply include the link—for example, "Have you considered using this specialized hash map: cool_hash.h?" This is also very useful for documentation, in bug reports, and in postmortems and is the canonical way of referring to code within Google. Even older versions of the code can be referenced, so links can stay valid as the codebase evolves.

What?

Roughly one quarter of Code Searches are classic file browsing, to answer the question of what a specific part of the codebase is doing. These kinds of tasks are usually more exploratory, rather than locating a specific result. This is using Code Search to read the source, to better understand code before making a change, or to be able to understand someone else’s change.

To ease these kinds of tasks, Code Search introduced browsing via call hierarchies and quick navigation between related files (e.g., between header, implementation, test, and build files). This is about understanding code by easily answering each of the many questions a developer has when looking at it.

How?

The most frequent use case—about one third of Code Searches—are about seeing examples of how others have done something. Typically, a developer has already found a specific API (e.g., how to read a file from remote storage) and wants to see how the API should be applied to a particular problem (e.g., how to set up the remote connection robustly and handle certain types of errors). Code Search is also used to find the proper library for specific problems in the first place (e.g., how to compute a fingerprint for integer values efficiently) and then pick the most appropriate implementation. For these kinds of tasks, a combination of searches and cross-reference browsing are typical.

Why?

Related to what code is doing, there are more targeted queries around why code is behaving differently than expected. About 16% of Code Searches try to answer the question of why a certain piece of code was added, or why it behaves in a certain way. Such questions often arise during debugging; for example, why does an error occur under these particular circumstances?

An important capability here is being able to search and explore the exact state of the codebase at a particular point in time. When debugging a production issue, this can mean working with a state of the codebase that is weeks or months old, while debugging test failures for new code usually means working with changes that are only minutes old. Both are possible with Code Search.

Who and When?

About 8% of Code Searches try to answer questions around who or when someone introduced a certain piece of code, interacting with the version control system. For example, it’s possible to see when a particular line was introduced (like Git’s "blame") and jump to the relevant code review. This history panel can also be very useful in finding the best person to ask about the code, or to review a change to it.6

Why a Separate Web Tool?

Outside Google, most of the aforementioned investigations are done within a local IDE. So, why yet another tool?

Scale

The first answer is that the Google codebase is so large that a local copy of the full codebase—a prerequisite for most IDEs—simply doesn’t fit on a single machine. Even before this fundamental barrier is hit, there is a cost to building local search and cross-reference indices for each developer, a cost often paid at IDE startup, slowing developer velocity. Or, without an index, one-off searches (e.g., with grep) can become painfully slow. A centralized search index means doing this work once, upfront, and means investments in the process benefit everyone. For example, the Code Search index is incrementally updated with every submitted change, enabling index construction with linear cost.7

In normal web search, fast-changing current events are mixed with more slowly changing items, such as stable Wikipedia pages. The same technique can be extended to searching code, making indexing incremental, which reduces its cost and allows changes to the codebase to be visible to everyone instantly. When a code change is submitted, only the actual files touched need to be reindexed, which allows parallel and independent updates to the global index.

Unfortunately, the cross-reference index cannot be instantly updated in the same way. Incrementality isn’t possible for it, as any code change can potentially influence the entire codebase, and in practice often does affect thousands of files. Many (nearly all of Google’s) full binaries need to be built8 (or at least analyzed) to determine the full semantic structure. It uses a ton of compute resources to produce the index daily (the current frequency). The discrepancy between the instant search index and the daily cross-reference index is a source of rare but recurring issues for users.

Zero Setup Global Code View

Being able to instantly and effectively browse the entire codebase means that it’s very easy to find relevant libraries to reuse and good examples to copy. For IDEs that construct indices at startup, there is a pressure to have a small project or visible scope to reduce this time and avoid flooding tools like autocomplete with noise. With the Code Search web UI, there is no setup required (e.g., project descriptions, build environment), so it’s also very easy and fast to learn about code, wherever it occurs, which improves developer efficiency. There’s also no danger of missing code dependencies; for example, when updating an API, reducing merge and library versioning issues.

Specialization

Perhaps surprisingly, one advantage of Code Search is that it is not an IDE. This means that the user experience (UX) can be optimized for browsing and understanding code, rather than editing it, which is usually the bulk of an IDE (e.g., keyboard shortcuts, menus, mouse clicks, and even screen space). For example, because there isn’t an editor’s text cursor, every mouse click on a symbol can be made meaningful (e.g., show all usages or jump to definition), rather than as a way to move the cursor. This advantage is so large that it’s extremely common for developers to have multiple Code Search tabs open at the same time as their editor.

Integration with Other Developer Tools

Because it is the primary way to view source code, Code Search is the logical platform for exposing information about source code. It frees up tool creators from needing to create a UI for their results and ensures the entire developer audience will know of their work without needing to advertise it. Many analyses run regularly over the entire Google codebase, and their results are usually surfaced in Code Search. For example, for many languages, we can detect "dead" (uncalled) code and mark it as such when the file is browsed.

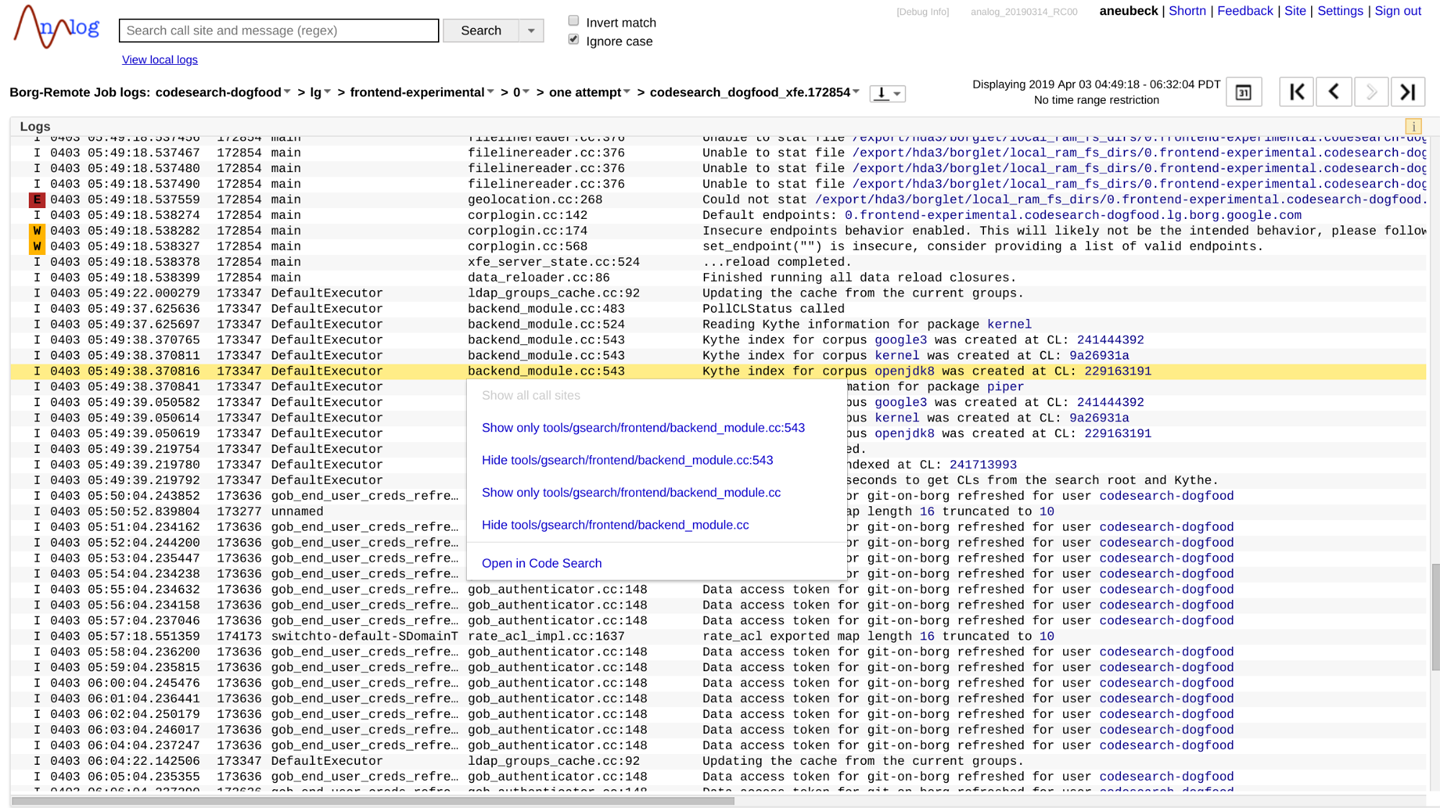

In the other direction, the Code Search link to a source file is considered its canonical “location.” This is useful for many developer tools (see Figure 17-2). For example, log file lines typically contain the filename and line number of the logging statement. The production log viewer uses a Code Search link to connect the log statement back to the producing code. Depending on the available information, this can be a direct link to a file at a specific revision, or a basic filename search with the corresponding line number. If there is only one matching file, it is opened at the corresponding line number. Otherwise, snippets of the desired line in each of the matching files are rendered.

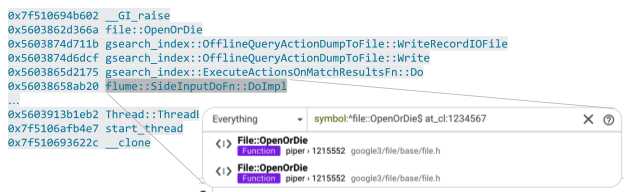

Similarly, stack frames are linked back to source code whether they are shown within a crash reporting tool or in log output, as shown in Figure 17-3. Depending on the programming language, the link will utilize a filename or symbol search. Because the snapshot of the repository at which the crashing binary was built is known, the search can actually be restricted to exactly this version. That way, links remain valid for a long time period, even if the corresponding code is later refactored or deleted.

Compilation errors and tests also typically refer back to a code location (e.g., test X in file at line). These can be linkified even for unsubmitted code given that most development happens in specific cloud-visible workspaces that are accessible and searchable by Code Search.

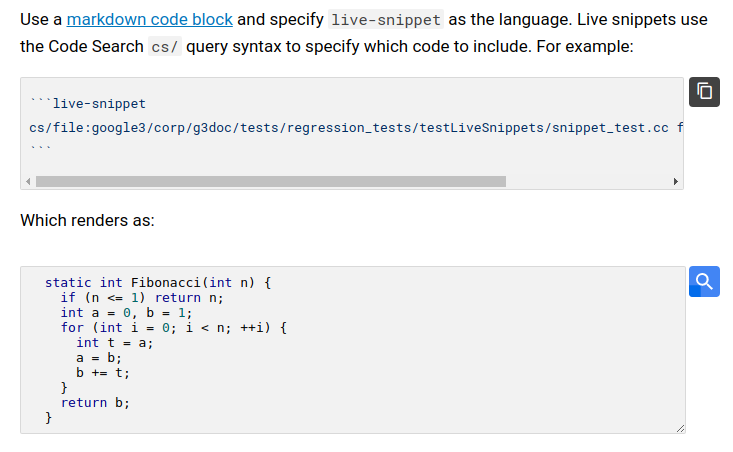

Finally, codelabs and other documentation refer to APIs, examples, and implementations. Such links can be search queries referencing a specific class or function, which remain valid when the file structure changes. For code snippets, the most recent implementation at head can easily be embedded into a documentation page, as demonstrated in Figure 17-4, without the need to pollute the source file with additional documentation markers.

API Exposure

Code Search exposes its search, cross-reference, and syntax highlighting APIs to tools, so tool developers can bring those capabilities into their tools without needing to reimplement them. Further, plug-ins have been written to provide search and cross-references to editors and IDEs such as vim, emacs, and IntelliJ. These plug-ins restore some of the power lost due to being unable to locally index the codebase, and give back some developer productivity.

Impact of Scale on Design

In the previous section, we looked at various aspects of the Code Search UI and why it’s worthwhile having a separate tool for browsing code. In the following sections, we look a bit behind the scenes of the implementation. We first discuss the primary challenge—scaling—and then some of the ways the large scale complicates making a good product for searching and browsing code. After that, we detail how we addressed some of those challenges, and what trade-offs were made when building Code Search.

The biggest9 scaling challenge for searching code is the corpus size. For a small repository of a couple megabytes, a brute-force search with grep search will do. When hundreds of megabytes need to be searched, a simple local index can speed up search by an order of magnitude or more. When gigabytes or terabytes of source code need to be searched, a cloud-hosted solution with multiple machines can keep search times reasonable. The utility of a central solution increases with the number of developers using it and the size of the code space.

Search Query Latency

Although we take as a given that a fast and responsive UI is better for the user, low latency doesn’t come for free. To justify the effort, one can weigh it against the saved engineering time across all users. Within Google, we process much more than one million search queries from developers within Code Search per day. For one million queries, an increase of just one second per search request corresponds to about 35 idle full-time engineers every day. In contrast, the search backend can be built and maintained with roughly a tenth of these engineers. This means that with about 100,000 queries per day (corresponding to less than 5,000 developers), just the one-second latency argument is something of a break-even point.

In reality, the productivity loss doesn’t simply increase linearly with latency. A UI is considered responsive if latencies are below 200 ms. But after just one second, the developer’s attention often begins to drift. If another 10 seconds pass, the developer is likely to switch context completely, which is generally recognized to have high productivity costs. The best way to keep a developer in the productive "flow" state is by targeting sub–200 ms end-to-end latency for all frequent operations and investing in the corresponding backends.

A large number of Code Search queries are performed in order to navigate the codebase. Ideally, the "next" file is only a click away (e.g., for included files, or symbol definitions), but for general navigation, instead of using the classical file tree, it can be much faster to simply search for the desired file or symbol, ideally without needing to fully specify it, and suggestions are provided for partial text. This becomes increasingly true as the codebase (and file tree) grows.

Normal navigation to a specific file in another folder or project requires several user interactions. With search, just a couple of keystrokes can be sufficient to get to the relevant file. To make search this effective, additional information about the search context (e.g., the currently viewed file) can be provided to the search backend. The context can restrict the search to files of a specific project, or influence ranking by preferring files that are in proximity to other files or directories. In the Code Search UI,10 the user can predefine multiple contexts and quickly switch between them as needed. In editors, the open or edited files are implicitly used as context to prioritize search results in their proximity.

One could consider the power of the search query language (e.g., specifying files, using regular expressions) as another criteria; we discuss this in the trade-offs section a little later in the chapter.

Index Latency

Most of the time, developers won’t notice when indices are out of date. They only care about a small subset of code, and even for that they generally won’t know whether there is more recent code. However, for the cases in which they wrote or reviewed the corresponding change, being out of sync can cause a lot of confusion. It tends not to matter whether the change was a small fix, a refactoring, or a completely new piece of code—developers simply expect a consistent view, such as they experience in their IDE for a small project.

When writing code, instant indexing of modified code is expected. When new files, functions, or classes are added, not being able to find them is frustrating and breaks the normal workflow for developers used to perfect cross-referencing. Another example are search-and-replace–based refactorings. It is not only more convenient when the removed code immediately disappears from the search results, but it is also essential that subsequent refactorings take the new state into account. When working with a centralized VCS, a developer might need instant indexing for submitted code if the previous change is no longer part of the locally modified file set.

Conversely, sometimes it’s useful to be able to go back in time to a previous snapshot of the code; in other words, a release. During an incident, a discrepancy between the index and the running code can be especially problematic because it can hide real causes or introduce irrelevant distractions. This is a problem for cross-references because the current technology for building an index at Google’s scale simply takes hours, and the complexity means that only one “version” of the index is kept. Although some patching can be done to align new code with an old index, this is still an issue to be solved.

Google’s Implementation

Google’s particular implementation of Code Search is tailored to the unique characteristics of its codebase, and the previous section outlined our design constraints for creating a robust and responsive index. The following section outlines how the Code Search team implemented and released its tool to Google developers.

Search Index

Google’s codebase is a special challenge for Code Search due to its sheer size. In the early days, a trigram-based approach was taken. Russ Cox subsequently open sourced a simplified version. Currently, Code Search indexes about 1.5 TB of content and processes about 200 queries per second with a median server-side search latency of less than 50 ms and a median indexing latency (time between code commit and visibility in the index) of less than 10 seconds.

Let’s roughly estimate the resource requirements to achieve this performance with a grep-based brute-force solution. The RE2 library we use for regular expression matching processes about 100 MB/sec for data in RAM. Given a time window of 50 ms, 300,000 cores would be needed to crunch through the 1.5 TB of data. Because in most cases simple substring searches are sufficient, one could replace the regular expression matching with a special substring search that can process about 1 GB/sec11 under certain conditions, reducing the number of cores by 10 times. So far, we have looked at just the resource requirements for processing a single query within 50 ms. If we’re getting 200 requests per second, 10 of those will be simultaneously active in that 50 ms window, bringing us back to 300,000 cores just for substring search.

Although this estimate ignores that the search can stop once a certain number of results are found or that file restrictions can be evaluated much more effectively than content searches, it doesn’t take communication overhead, ranking, or the fan out to tens of thousands of machines into account either. But it shows quite well the scale involved and why Google’s Code Search team continuously invests into improving indexing. Over the years, our index changed from the original trigram-based solution, through a custom suffix array–based solution, to the current sparse n-gram solution. This latest solution is more than 500 times more efficient than the brute-force solution while being capable of also answering regular expression searches at blazing speed.

One reason we moved from a suffix array–based solution to a token-based n-gram solution was to take advantage of Google’s primary indexing and search stack. With a suffix array–based solution, building and distributing the custom indices becomes a challenge in and of itself. By utilizing "standard" technology, we benefit from all the advances in reverse index construction, encoding, and serving made by the core search team. Instant indexing is another feature that exists in standard search stacks, and by itself is a big challenge when solving it at scale.

Relying on standard technology is a trade-off between implementation simplicity and performance. Even though Google’s Code Search implementation is based on standard reverse indices, the actual retrieval, matching, and scoring are highly customized and optimized. Some of the more advanced Code Search features wouldn’t be possible otherwise. To index the history of file revisions, we came up with a custom compression scheme in which indexing the full history increased the resource consumption by a factor of just 2.5.

In the early days, Code Search served all data from memory. With the growing index size, we moved the inverted index to flash. Although flash storage is at least an order of magnitude cheaper than memory, its access latency is at least two orders of magnitude higher. So, indices that work well in memory might not be suitable when served from flash. For instance, the original trigram index requires fetching not only a large number of reverse indices from flash, but also quite large ones. With n-gram schemes, both the number of inverse indices and their size can be reduced at the expense of a larger index.

To support local workspaces (which have a small delta from the global repository), we have multiple machines doing simple brute-force searches. The workspace data is loaded on the first request and then kept in sync by listening for file changes. When we run out of memory, we remove the least recent workspace from the machines. The unchanged documents are searched with our history index. Therefore, the search is implicitly restricted to the repository state to which the workspace is synced.

Ranking

For a very small codebase, ranking doesn’t provide much benefit, because there aren’t many results anyway. But the larger the codebase becomes, the more results will be found and the more important ranking becomes. In Google’s codebase, any short substring will occur thousands, if not millions, of times. Without ranking, the user either must check all of those results in order to find the correct one, or must refine the query12 further until the result set is reduced to just a handful of files. Both options waste the developer’s time.

Ranking typically starts with a scoring function, which maps a set of features of each file ("signals") to some number: the higher the score, the better the result. The goal of the search is then to find the top N results as efficiently as possible. Typically, one distinguishes between two types of signals: those that depend only on the document (“query independent”) and those that depend on the search query and how it matches the document (“query dependent”). The filename length or the programming language of a file would be examples of query independent signals, whereas whether a match is a function definition or a string literal is a query dependent signal.

Query independent signals

Some of the most important query independent signals are the number of file views and the amount of references to a file. File views are important because they indicate which files developers consider important and are therefore more likely to want to find. For instance, utility functions in base libraries have a high view count. It doesn’t matter whether the library is already stable and isn’t changed anymore or whether the library is being actively developed. The biggest downside of this signal is the feedback loop it creates. By scoring frequently viewed documents higher, the chance increases that developers will look at them and decreases the chance of other documents to make it into the top N. This problem is known as exploitation versus exploration, for which various solutions exist (e.g., advanced A/B search experiments or curation of training data). In practice, it doesn’t seem harmful to somewhat over-show high-scoring items: they are simply ignored when irrelevant and taken if a generic example is needed. However, it is a problem for new files, which don’t yet have enough information for a good signal.13

We also use the number of references to a file, which parallels the original page rank algorithm, by replacing web links as references with the various kinds of "include/import" statements present in most languages. We can extend the concept up to build dependencies (library/module level references) and down to functions and classes. This global relevance is often referred to as the document’s "priority."

When using references for ranking, one must be aware of two challenges. First, you must be able to extract reference information reliably. In the early days, Google’s Code Search extracted include/import statements with simple regular expressions and then applied heuristics to convert them into full file paths. With the growing complexity of a codebase, such heuristics became error prone and challenging to maintain. Internally, we replaced this part with correct information from the Kythe graph.

Large-scale refactorings, such as open sourcing core libraries, present a second challenge. Such changes don’t happen atomically in a single code update; rather, they need to be rolled out in multiple stages. Typically, indirections are introduced, hiding, for example, the move of files from usages. These kinds of indirections reduce the page rank of moved files and make it more difficult for developers to discover the new location. Additionally, file views usually become lost when files are moved, making the situation even worse. Because such global restructurings of the codebase are comparatively rare (most interfaces move rarely), the simplest solution is to manually boost files during such transition periods. (Or wait until the migration completes and for the natural processes to up-rank the file in its new location.)

Query dependent signals

Query independent signals can be computed offline, so computational cost isn’t a major concern, although it can be high. For example, for the "page" rank, the signal depends on the whole corpus and requires a MapReduce-like batch processing to calculate. Query dependent signals, which must be calculated for each query, should be cheap to compute. This means that they are restricted to the query and information quickly accessible from the index.

Unlike web search, we don’t just match on tokens. However, if there are clean token matches (that is, the search term matches with content with some form of breaks, such as whitespace, around it), a further boost is applied and case sensitivity is considered. This means, for example, a search for "Point" will score higher against "Point *p" than against "appointed to the council."

For convenience, a default search matches filename and qualified symbols14 in addition to the actual file content. A user can specify the particular kind of match, but they don’t need to. The scoring boosts symbol and filename matches over normal content matches to reflect the inferred intent of the developer. Just as with web searches, developers can add more terms to the search to make queries more specific. It’s very common for a query to be “qualified” with hints about the filename (e.g., "base" or "myproject"). Scoring leverages this by boosting results where much of the query occurs in the full path of the potential result, putting such results ahead of those that contain only the words in random places in their content.

Retrieval

Before a document can be scored, candidates that are likely to match the search query are found. This phase is called retrieval. Because it is not practical to retrieve all documents, but only retrieved documents can be scored, retrieval and scoring must work well together to find the most relevant documents. A typical example is to search for a class name. Depending on the popularity of the class, it can have thousands of usages, but potentially only one definition. If the search was not explicitly restricted to class definitions, retrieval of a fixed number of results might stop before the file with the single definition was reached. Obviously, the problem becomes more challenging as the codebase grows.

The main challenge for the retrieval phase is to find the few highly relevant files among the bulk of less interesting ones. One solution that works quite well is called supplemental retrieval. The idea is to rewrite the original query into more specialized ones. In our example, this would mean that a supplemental query would restrict the search to only definitions and filenames and add the newly retrieved documents to the output of the retrieval phase. In a naive implementation of supplemental retrieval, more documents need to be scored, but the additional partial scoring information gained can be used to fully evaluate only the most promising documents from the retrieval phase.

Result diversity

Another aspect of search is diversity of results, meaning trying to give the best results in multiple categories. A simple example would be to provide both the Java and Python matches for a simple function name, rather than filling the first page of results with one or the other.

This is especially important when the intent of the user is not clear. One of the challenges with diversity is that there are many different categories—like functions, classes, filenames, local results, usages, tests, examples, and so on—into which results can be grouped, but that there isn’t a lot of space in the UI to show results for all of them or even all combinations, nor would it always be desirable. Google’s Code Search doesn’t do this as well as web search does, but the drop-down list of suggested results (like the autocompletions of web search) is tweaked to provide a diverse set of top filenames, definitions, and matches in the user’s current workspace.

Selected Trade-Offs

Implementing Code Search within a codebase the size of Google’s—and keeping it responsive—involved making a variety of trade-offs. These are noted in the following section.

Completeness: Repository at Head

We’ve seen that a larger codebase has negative consequences for search; for example, slower and more expensive indexing, slower queries, and noisier results. Can these costs be reduced by sacrificing completeness; in other words, leaving some content out of the index? The answer is yes, but with caution. Nontext files (binaries, images, videos, sound, etc.) are usually not meant to be read by humans and are dropped apart from their filename. Because they are huge, this saves a lot of resources. A more borderline case involves generated JavaScript files. Due to obfuscation and the loss of structure, they are pretty much unreadable for humans, so excluding them from the index is usually a good trade-off, reducing indexing resources and noise at the cost of completeness. Empirically, multimegabyte files rarely contain information relevant for developers, so excluding extreme cases is probably the correct choice.

However, dropping files from the index has one big drawback. For developers to rely on Code Search, they need to be able to trust it. Unfortunately, it is generally impossible to give feedback about incomplete search results for a specific search if the dropped files weren’t indexed in the first place. The resulting confusion and productivity loss for developers is a high price to pay for the saved resources. Even if developers are fully aware of the limitations, if they still need to perform their search, they will do so in an ad hoc and error-prone way. Given these rare but potentially high costs, we choose to err on the side of indexing too much, with quite high limits that are mostly picked to prevent abuse and guarantee system stability rather than to save resources.

In the other direction, generated files aren’t in the codebase but would often be useful to index. Currently they are not, because indexing them would require integrating the tools and configuration to create them, which would be a massive source of complexity, confusion, and latency.

Completeness: All Versus Most-Relevant Results

Normal search sacrifices completeness for speed, essentially gambling that ranking will ensure that the top results will contain all of the desired results. And indeed, for Code Search, ranked search is the more common case in which the user is looking for one particular thing, such as a function definition, potentially among millions of matches. However, sometimes developers want all results; for example, finding all occurrences of a particular symbol for refactoring. Needing all results is common for analysis, tooling, or refactoring, such as a global search and replace. The need to deliver all results is a fundamental difference to web search in which many shortcuts can be taken, such as to only consider highly ranked items.

Being able to deliver all results for very large result sets has high cost, but we felt it was required for tooling, and for developers to trust the results. However, because for most queries only a few results are relevant (either there are only a few matches15 or only a few are interesting), we didn’t want to sacrifice average speed for potential completeness.

To achieve both goals with one architecture, we split the codebase into shards with files ordered by their priority. Then, we usually need to consider only the matches to high priority files from each chunk. This is similar to how web search works. However, if requested, Code Search can fetch all results from each chunk, to guarantee finding all results.16 This lets us address both use cases, without typical searches being slowed down by the less frequently used capability of returning large, complete results sets. Results can also then be delivered in alphabetical order, rather than ranked, which is useful for some tools.

So, here the trade-off was a more complex implementation and API versus greater capabilities, rather than the more obvious latency versus completeness.

Completeness: Head Versus Branches Versus All History Versus Workspaces

Related to the dimension of corpus size is the question of which code versions should be indexed: specifically, whether anything more than the current snapshot of code ("head") should be indexed. System complexity, resource consumption, and overall cost increase drastically if more than a single file revision is indexed. To our knowledge, no IDE indexes anything but the current version of code. When looking at distributed version control systems like Git or Mercurial, a lot of their efficiency comes from the compression of their historical data. But the compactness of these representations becomes lost when constructing reverse indices. Another issue is that it is difficult to efficiently index graph structures, which are the basis for Distributed Version Control Systems.

Although it is difficult to index multiple versions of a repository, doing so allows the exploration of how code has changed and finding deleted code. Within Google, Code Search indexes the (linear) Piper history. This means that the codebase can be searched at an arbitrary snapshot of the code, for deleted code, or even for code authored by certain people.

One big benefit is that obsolete code can now simply be deleted from the codebase. Before, code was often moved into directories marked as obsolete so that it could still be found later. The full history index also laid the foundation for searching effectively in people’s workspaces (unsubmitted changes), which are synced to a specific snapshot of the codebase. For the future, a historical index opens up the possibility of interesting signals to use when ranking, such as authorship, code activity, and so on.

Workspaces are very different from the global repository:

-

Each developer can have their own workspaces.

-

There are usually a small number of changed files within a workspace.

-

The files being worked on are changing frequently.

-

A workspace exists only for a relatively short time period.

To provide value, a workspace index must reflect exactly the current state of the workspace.

Expressiveness: Token Versus Substring Versus Regex

The effect of scale is greatly influenced by the supported search feature set. Code Search supports regular expression (regex) search, which adds power to the query language, allowing whole groups of terms to be specified or excluded, and they can be used on any text, which is especially helpful for documents and languages for which deeper semantic tools don’t exist.

Developers are also used to using regular expressions in other tools (e.g., grep) and contexts, so they provide powerful search without adding to a developer’s cognitive load. This power comes at a cost given that creating an index to query them efficiently is challenging. What simpler options exist?

A token-based index (i.e., words) scales well because it stores only a fraction of the actual source code and is well supported by standard search engines. The downside is that many use cases are tricky or even impossible to realize efficiently with a token-based index when dealing with source code, which attaches meaning to many characters typically ignored when tokenizing. For example, searching for "function()" versus "function(x)", "(x ^ y)", or "=== myClass" is difficult or impossible in most token-based searches.

Another problem of tokenization is that tokenization of code identifiers is ill defined. Identifiers can be written in many ways, such as CamelCase, snake_case, or even justmashedtogether without any word separator. Finding an identifier when remembering only some of the words is a challenge for a token-based index.

Tokenization also typically doesn’t care about the case of letters ("r" versus "R"), and will often blur words; for example, reducing "searching" and "searched" to the same stem token search. This lack of precision is a significant problem when searching code. Finally, tokenization makes it impossible to search on whitespace or other word delimiters (commas, parentheses), which can be very important in code.

A next step up17 in searching power is full substring search in which any sequence of characters can be searched for. One fairly efficient way to provide this is via a trigram-based index.18 In its simplest form, the resulting index size is still much smaller than the original source code size. However, the small size comes at the cost of relatively low recall accuracy compared to other substring indices. This means slower queries because the nonmatches need to be filtered out of the result set. This is where a good compromise between index size, search latency, and resource consumption must be found that depends heavily on codebase size, resource availability, and searches per second.

If a substring index is available, it’s easy to extend it to allow regular expression searches. The basic idea is to convert the regular expression automaton into a set of substring searches. This conversion is straightforward for a trigram index and can be generalized to other substring indices. Because there is no perfect regular expression index, it will always be possible to construct queries that result in a brute-force search. However, given that only a small fraction of user queries are complex regular expressions, in practice, the approximation via substring indices works very well.

Conclusion

Code Search grew from an organic replacement for grep into a central tool boosting developer productivity, leveraging Google’s web search technology along the way. What does this mean for you, though? If you are on a small project that easily fits in your IDE, probably not much. If you are responsible for the productivity of engineers on a larger codebase, there are probably some insights to be gained.

The most important one is perhaps obvious: understanding code is key to developing and maintaining it, and this means that investing in understanding code will yield dividends that might be difficult to measure, but are real. Every feature we added to Code Search was and is used by developers to help them in their daily work (admittedly some more than others). Two of the most important features, Kythe integration (i.e., adding semantic code understanding) and finding working examples, are also the most clearly tied to understanding code (versus, for example, finding it, or seeing how it’s changed). In terms of tool impact, no one uses a tool that they don’t know exists, so it is also important to make developers aware of the available tooling—at Google, it is part of "Noogler" training, the onboarding training for newly hired software engineers.

For you, this might mean setting up a standard indexing profile for IDEs, sharing knowledge about egrep, running ctags, or setting up some custom indexing tooling, like Code Search. Whatever you do, it will almost certainly be used, and used more, and in different ways than you expected—and your developers will benefit.

TL;DRs

-

Helping your developers understand code can be a big boost to engineering productivity. At Google, the key tool for this is Code Search.

-

Code Search has additional value as a basis for other tools and as a central, standard place that all documentation and developer tools link to.

-

The huge size of the Google codebase made a custom tool—as opposed to, for example,

grepor an IDE’s indexing—necessary. -

As an interactive tool, Code Search must be fast, allowing a "question and answer" workflow. It is expected to have low latency in every respect: search, browsing, and indexing.

-

It will be widely used only if it is trusted, and will be trusted only if it indexes all code, gives all results, and gives the desired results first. However, earlier, less powerful, versions were both useful and used, as long as their limits were understood.

1GSearch originally ran on Jeff Dean’s personal computer, which once caused company-wide distress when he went on vacation and it was shut down!

2Shut down in 2013; see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Code_Search.

3Now known as Kythe, a service that provides cross-references (among other things): the uses of a particular code symbol—for example, a function—using the full build information to disambiguate it from other ones with the same name.

4There is an interesting virtuous cycle that a ubiquitous code browser encourages: writing code that is easy to browse. This can mean things like not nesting hierarchies too deep, which requires many clicks to move from call sites to actual implementation, and using named types rather than generic things like strings or integers, because it’s then easy to find all usages.

5Sadowski, Caitlin, Kathryn T. Stolee, and Sebastian Elbaum. “How Developers Search for Code: A Case Study” In Proceedings of the 2015 10th Joint Meeting on Foundations of Software Engineering (ESEC/FSE 2015). https://doi.org/10.1145/2786805.2786855.

6That said, given the rate of commits for machine-generated changes, naive “blame” tracking has less value than it does in more change-averse ecosystems.

7For comparison, the model of “every developer who has their own IDE on their own workspace should do the indexing calculation” scales roughly quadratically: developers produce a roughly constant amount of code per unit time, so the codebase scales linearly (even with a fixed number of developers). A linear number of IDEs do linearly more work each time—this is not a recipe for good scaling.

8Kythe instruments the build workflow to extract semantic nodes and edges from source code. This extraction process collects partial cross-reference graphs for each individual build rule. In a subsequent phase, these partial graphs are merged into one global graph and its representation is optimized for the most common queries (go-to-definition, find all usages, fetch all decorations for a file). Each phase—extraction and post processing—is roughly as expensive as a full build; for example, in case of Chromium, the construction of the Kythe index is done in about six hours in a distributed setup and therefore too costly to be constructed by every developer on their own workstation. This computational cost is the why the Kythe index is computed only once per day.

9Because queries are independent, more users can be addressed by having more servers.

10The Code Search UI does also have a classical file tree, so navigating this way is also possible.

11See https://blog.scalyr.com/2014/05/searching-20-gbsec-systems-engineering-before-algorithms and http://volnitsky.com/project/str_search.

12In contrast to web search, adding more characters to a Code Search query always reduces the result set (apart from a few rare exceptions via regular expression terms).

13This could likely be somewhat corrected by using recency in some form as a signal, perhaps doing something similar to web search dealing with new pages, but we don’t yet do so.

14In programming languages, a symbol such as a function "Alert" often is defined in a particular scope, such as a class ("Monitor") or namespace ("absl"). The qualified name might then be absl::Monitor::Alert, and this is findable, even if it doesn’t occur in the actual text.

15An analysis of queries showed that about one-third of user searches have fewer than 20 results.

16In practice, even more happens behind the scenes so that responses don’t become painfully huge and developers don’t bring down the whole system by making searches that match nearly everything (imagine searching for the letter “i” or a single space).

17There are other intermediate varieties, such as building a prefix/suffix index, but generally they provide less expressiveness in search queries while still having high complexity and indexing costs.

18Russ Cox, “Regular Expression Matching with a Trigram Index or How Google Code Search Worked.”